Business

Freedom and fear: the foundations of America’s deadly gun culture

Published

2 years agoon

By

AFP

It was 1776, the American colonies had just declared their independence from England, and as war raged the founding fathers were deep in debate: should Americans have the right to own firearms as individuals, or just as members of local militia?

As a landmark Supreme Court decision expanded gun rights Thursday, just weeks after a mass killing of 19 children in their Texas school, the debate rages on and outsiders wonder why Americans are so wedded to the firearms used in such massacres with appalling frequency.

The answer, experts say, lies both in the traditions underpinning the country’s winning its freedom from Britain, and most recently, a growing belief among consumers that they need guns for their personal safety.

Over the past two decades — a period in which more than 200 million guns hit the US market — the country has shifted from “Gun Culture 1.0,” where guns were for sport and hunting, to “Gun Culture 2.0” where many Americans see them as essential to protect their homes and families.

That shift has been driven heavily by advertising by the nearly $20 billion gun industry that has tapped fears of crime and racial upheaval, according to Ryan Busse, a former industry executive.

Recent mass murders “are the byproduct of a gun industry business model designed to profit from increasing hatred, fear, and conspiracy,” Busse wrote in May in the online magazine The Bulwark.

Yet in the wake of the May mass shootings of Black people at a supermarket in New York state and children and teachers at their school in Uvalde, Texas, consensus emerged for US lawmakers to advance some modest new gun control measures.

Nearly simultaneously the US Supreme Court struck down Thursday a New York state law restricting who can carry a firearm, a significant expansion of gun rights.

– Guns and the new nation –

For the men designing the new United States in the 1770s and 1780s, there was no question about gun ownership.

They said the monopoly on guns by the monarchies of Europe and their armies was the very source of oppression that the American colonists were fighting.

James Madison, the “father of the constitution,” cited “the advantage of being armed, which the Americans possess over the people of almost every other nation.”

But he and the other founders understood the issue was complex. The new states did not trust the nascent federal government, and wanted their own laws, and own arms.

They recognized people needed to hunt and protect themselves against wild animals and thieves. But some worried more private guns could just increase frontier lawlessness.

Were private guns essential to protect against tyranny? Couldn’t local armed militia fulfil that role? Or would militia become a source of local oppression?

In 1791, a compromise was struck in what has become the most parsed phrase in the Constitution, the Second Amendment guaranteeing gun rights:

“A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.”

– 1960s gun control –

Over the following two centuries, guns became an essential part of American life and myth.

Gun Culture 1.0, as Wake Forest University professor David Yamane describes it, was about guns as critical tools for pioneers hunting game and fending off varmints — as well as the genocidal conquest of native Americans and the control of slaves.

But by the early 20th century, the increasingly urbanized United States was awash with firearms and experiencing notable levels of gun crime not seen in other countries.

From 1900 to 1964, wrote the late historian Richard Hofstadter, the country recorded more than 265,000 gun homicides, 330,000 suicides, and 139,000 gun accidents.

In reaction to a surge in organized crime violence, in 1934 the federal government banned machine guns and required guns to be registered and taxed.

Individual states added their own controls, like bans on carrying guns in public, openly or concealed.

The public was for such controls: pollster Gallup says that in 1959, 60 percent of Americans supported a complete ban on personal handguns.

The assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, brought a push for strenuous regulation in 1968.

But gunmakers and the increasingly assertive National Rifle Association, citing the Second Amendment, prevented new legislation from doing more than implement an easily circumvented restriction on direct mail-order gun sales.

– The holy Second Amendment –

Over the next two decades, the NRA built common cause with Republicans to insist that the Second Amendment was absolute in its protection of gun rights, and that any regulation was an attack on Americans’ “freedom.”

According to Matthew Lacombe, a Barnard College professor, achieving that involved the NRA creating and advertising a distinct gun-centric ideology and social identity for gun owners.

Gun owners banded together around that ideology, forming a powerful voting bloc, especially in rural areas that Republicans sought to seize from Democrats.

Jessica Dawson, a professor at the West Point military academy, said the NRA made common cause with the religious right, a group that believes in Christianity’s primacy in American culture and the constitution.

Drawing “on the New Christian Right’s belief in moral decay, distrust of the government, and belief in evil,” the NRA leadership “began to use more religiously coded language to elevate the Second Amendment above the restrictions of a secular government,” Dawson wrote.

– Self-defense –

Yet the shift of focus to the Second Amendment did not help gunmakers, who saw flat sales due to the steep decline by the 1990s in hunting and shooting sports.

That paved the way for Gun Culture 2.0 — when the NRA and the gun industry began telling consumers that they needed personal firearms to protect themselves, according to Busse.

Gun marketing increasingly showed people under attack from rioters and thieves, and hyped the need for personal “tactical” equipment.

The timing paralleled Barack Obama becoming the first African American president and a rise in white nationalism.

“Fifteen years ago, at the behest of the NRA, the firearms industry took a dark turn when it started marketing increasingly aggressive and militaristic guns and tactical gear,” Busse wrote.

Meanwhile, many states answered worries about a perceived rise in crime by allowing people to carry guns in public without permits.

In fact, violent crime has trended downward over the past two decades — though gun-related killings have surged in recent years.

That, said Wake Forest’s Yamane, was a key turning point for Gun Culture 2.0, giving a sharp boost to handgun sales, which people of all races bought, amid exaggerated fears of internecine violence.

Since 2009, sales have soared, topping more than 10 million a year since 2013, mainly AR-15-type assault rifles and semi-automatic pistols.

“The majority of gun owners today — especially new gun owners — point to self-defense as the primary reason for owning a gun,” Yamane wrote.

With 2,400 staff representing 100 different nationalities, AFP covers the world as a leading global news agency. AFP provides fast, comprehensive and verified coverage of the issues affecting our daily lives.

You may like

-

‘Early-stage’ AI begins to make waves at China sex toy expo

-

UK PM Sunak promises action against Chinese cyberattacks

-

TikTok and its ‘secret sauce’ caught in US-China tussle

-

TikTok devotees say platform unfairly targeted for US ban

-

Brazil seeks to curb AI deepfakes as key elections loom

-

US lawmakers push for TikTok to cut ByteDance ties or face ban

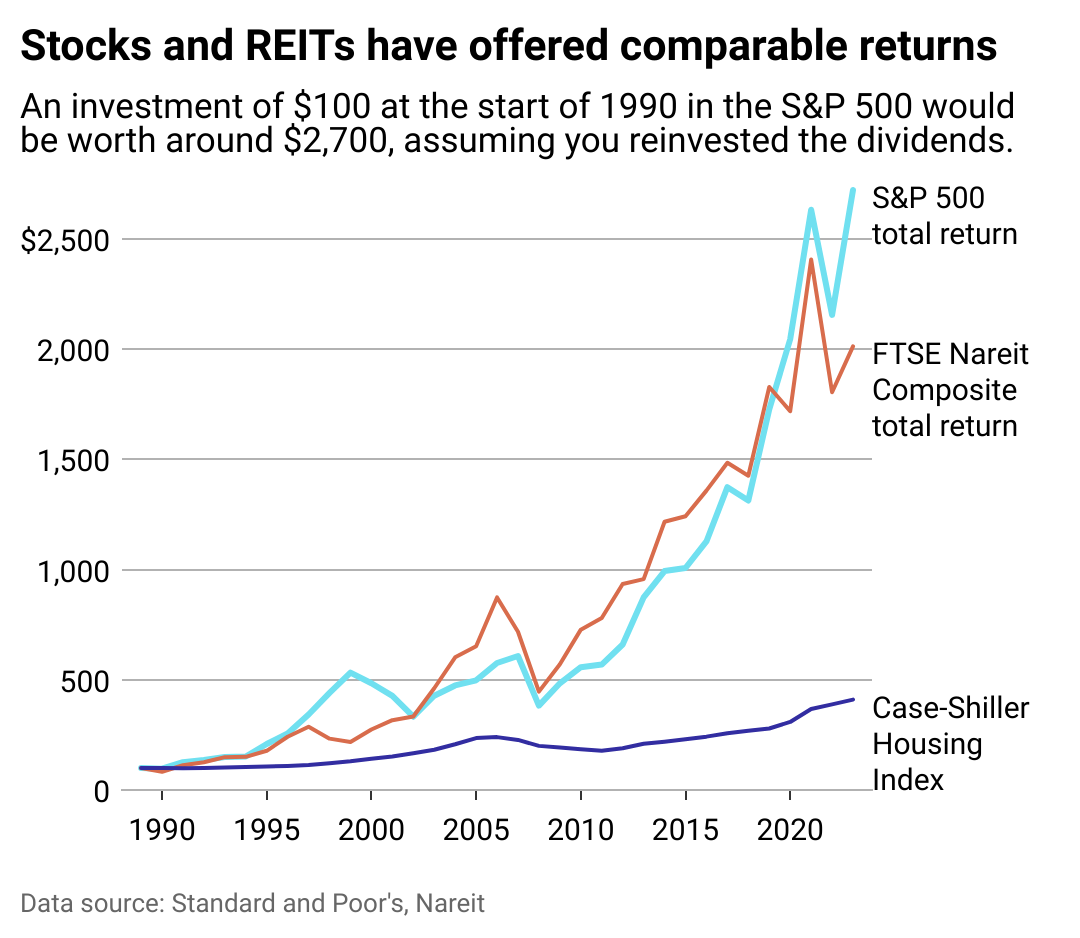

It’s well-documented that the surest, and often best, return on investments comes from playing the long game. But between stocks and real estate, which is the stronger bet?

To find out, financial planning firm Wealth Enhancement Group analyzed data from academic research, Standard and Poor’s, and Nareit to see how real estate compares to stocks as an investment.

Data going back to 1870 shows the well-established power of real estate as a powerful “long-run investment.” From 1870-2015, and after adjusting for inflation, real estate produced an average annual return of 7.05%, compared to 6.89% for equities. These findings, published in the 2019 issue of The Quarterly Journal of Economics, illustrate that stocks can deviate as much as 22% from their average, while housing only spreads out 10%. That’s because despite having comparable returns, stocks are inherently more volatile due to following the whims of the business cycle.

Real estate has inherent benefits, from unlocking cash flow and offering tax breaks to building equity and protecting investors from inflation. Investments here also help to diversify a portfolio, whether via physical properties or a real estate investment trust. Investors can track markets with standard resources that include the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Home Price Indices, which tracks residential real estate prices; the Nareit U.S. Real Estate Index, which gathers data on the real estate investment trust, or REIT, industry; and the S&P 500, which tracks the stocks of 500 of the largest companies in the U.S.

High interest rates and a competitive market dampened the flurry of real-estate investments made in the last four years. The rise in interest rates equates to a bigger borrowing cost for investors, which can spell big reductions in profit margins. That, combined with the risk of high vacancies, difficult tenants, or hidden structural problems, can make real estate investing a less attractive option—especially for first-time investors.

Keep reading to learn more about whether real estate is a good investment today and how it stacks up against the stock market.

![]()

Wealth Enhancement Group

Stocks and housing have both done well

REITs can offer investors the stability of real estate returns without bidding wars or hefty down payments. A hybrid model of stocks and real estate, REITs allow the average person to invest in businesses that finance or own income-generating properties.

REITs delivered slightly better returns than the S&P 500 over the past 20-, 25-, and 50-year blocks. However, in the short term—the last 10 years, for instance—stocks outperformed REITs with a 12% return versus 9.5%, according to data compiled by The Motley Fool investor publication.

Whether a new normal is emerging that stocks will continue to offer higher REITs remains to be seen.

This year, the S&P 500 reached an all-time high, courtesy of investor enthusiasm in speculative tech such as artificial intelligence. However, just seven tech companies, dubbed “The Magnificent 7,” are responsible for an outsized amount of the S&P’s returns last year, creating worry that there may be a tech bubble.

While indexes keep a pulse on investment performance, they don’t always tell the whole story. The Case-Shiller Index only measures housing prices, for example, which leaves out rental income (profit) or maintenance costs (loss) when calculating the return on residential real estate investment.

Wealth Enhancement Group

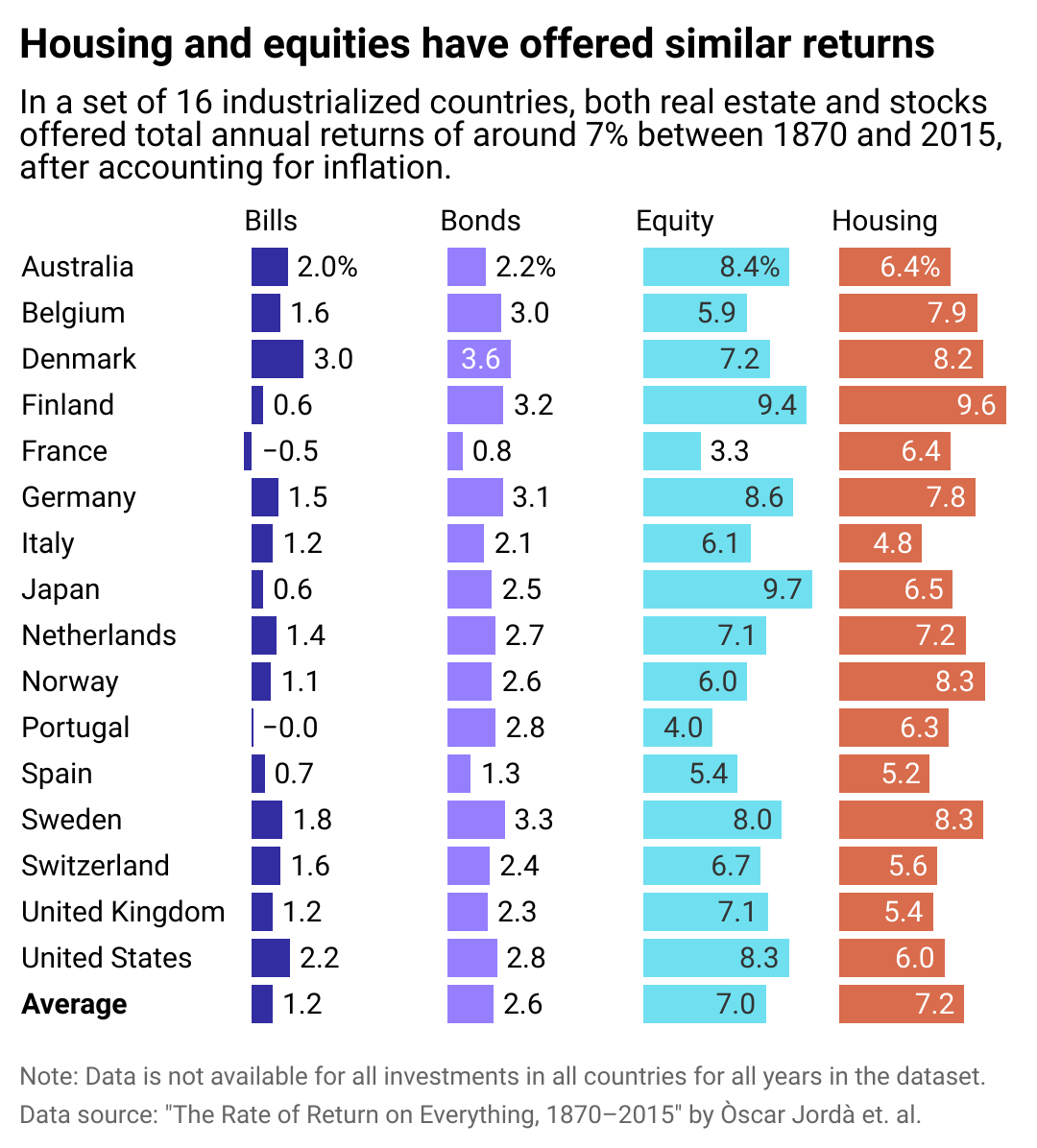

Housing returns have been strong globally too

Like its American peers, the global real estate market in industrialized nations offers comparable returns to the international stock market.

Over the long term, returns on stocks in industrialized nations is 7%, including dividends, and 7.2% in global real estate, including rental income some investors receive from properties. Investing internationally may have more risk for American buyers, who are less likely to know local rules and regulations in foreign countries; however, global markets may offer opportunities for a higher return. For instance, Portugal’s real estate market is booming due to international visitors deciding to move there for a better quality of life. Portugal’s housing offers a 6.3% return in the long term, versus only 4.3% for its stock market.

For those with deep enough pockets to stay in, investing in housing will almost always bear out as long as the buyer has enough equity to manage unforeseen expenses and wait out vacancies or slumps in the market. Real estate promises to appreciate over the long term, offers an opportunity to collect rent for income, and allows investors to leverage borrowed capital to increase additional returns on investment.

Above all, though, the diversification of assets is the surest way to guarantee a strong return on investments. Spreading investments across different assets increases potential returns and mitigates risk.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Wealth Enhancement Group and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Business

5 tech advancements sports venues have added since your last event

Published

4 days agoon

April 19, 2024

In today’s digital climate, consuming sports has never been easier. Thanks to a plethora of streaming sites, alternative broadcasts, and advancements to home entertainment systems, the average fan has myriad options to watch and learn about their favorite teams at the touch of a button—all without ever having to leave the couch.

As a result, more and more sports venues have committed to improving and modernizing their facilities and fan experiences to compete with at-home audiences. Consider using mobile ticketing and parking passes, self-service kiosks for entry and ordering food, enhanced video boards, and jumbotrons that supply data analytics and high-definition replays. These innovations and upgrades are meant to draw more revenue and attract various sponsored partners. They also deliver unique and convenient in-person experiences that rival and outmatch traditional ways of enjoying games.

In Los Angeles, the Rams and Chargers’ SoFi Stadium has become the gold standard for football venues. It’s an architectural wonder with closer views, enhanced hospitality, and a translucent roof that cools the stadium’s internal temperature.

The Texas Rangers’ ballpark, Globe Life Field, added field-level suites and lounges that resemble the look and feel of a sports bar. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Clippers are building a new arena (in addition to retail space, team offices, and an outdoor public plaza) that will seat 18,000 people and feature a fan section called The Wall, which will regulate attire and rooting interest.

It’s no longer acceptable to operate with old-school facilities and technology. Just look at Commanders Field (formerly FedExField), home of the Washington Commanders, which has faced criticism for its faulty barriers, leaking ceilings, poor food options, and long lines. Understandably, the team has been attempting to find a new location to build a state-of-the-art stadium and keep up with the demand for high-end amenities.

As more organizations audit their stadiums and arenas and keep up with technological innovations, Uniqode compiled a list of the latest tech advancements to coax—and keep—fans inside venues.

![]()

Jeff Gritchen/MediaNews Group/Orange County Register // Getty Images

Just Walk Out technology

After successfully installing its first cashierless grocery store in 2020, Amazon has continued to put its tracking technology into practice.

In 2023, the Seahawks incorporated Just Walk Out technology at various merchandise stores throughout Lumen Field, allowing fans to purchase items with a swipe and scan of their palms.

The radio-frequency identification system, which involves overhead cameras and computer vision, is a substitute for cashiers and eliminates long lines.

RFID is now found in a handful of stadiums and arenas nationwide. These stores have already curbed checkout wait times, eliminated theft, and freed up workers to assist shoppers, according to Jon Jenkins, vice president of Just Walk Out tech.

Billie Weiss/Boston Red Sox // Getty Images

Self-serve kiosks

In the same vein as Amazon’s self-scanning technology, self-serve kiosks have become a more integrated part of professional stadiums and arenas over the last few years. Some of these function as top-tier vending machines with canned beers and nonalcoholic drinks, shuffling lines quicker with virtual bartenders capable of spinning cocktails and mixed drinks.

The kiosks extend past beverages, as many college and professional venues have started using them to scan printed and digital tickets for more efficient entrance. It’s an effort to cut down lines and limit the more tedious aspects of in-person attendance, and it’s led various competing kiosk brands to provide their specific conveniences.

Kyle Rivas // Getty Images

Mobile ordering

Is there anything worse than navigating the concourse for food and alcohol and subsequently missing a go-ahead home run, clutch double play, or diving catch?

Within the last few years, more stadiums have eliminated those worries thanks to contactless mobile ordering. Fans can select food and drink items online on their phones to be delivered right to their seats. Nearly half of consumers said mobile app ordering would influence them to make more restaurant purchases, according to a 2020 study at PYMNTS. Another study showed a 22% increase in order size.

Many venues, including Yankee Stadium, have taken notice and now offer personalized deliveries in certain sections and established mobile order pick-up zones throughout the ballpark.

Darrian Traynor // Getty Images

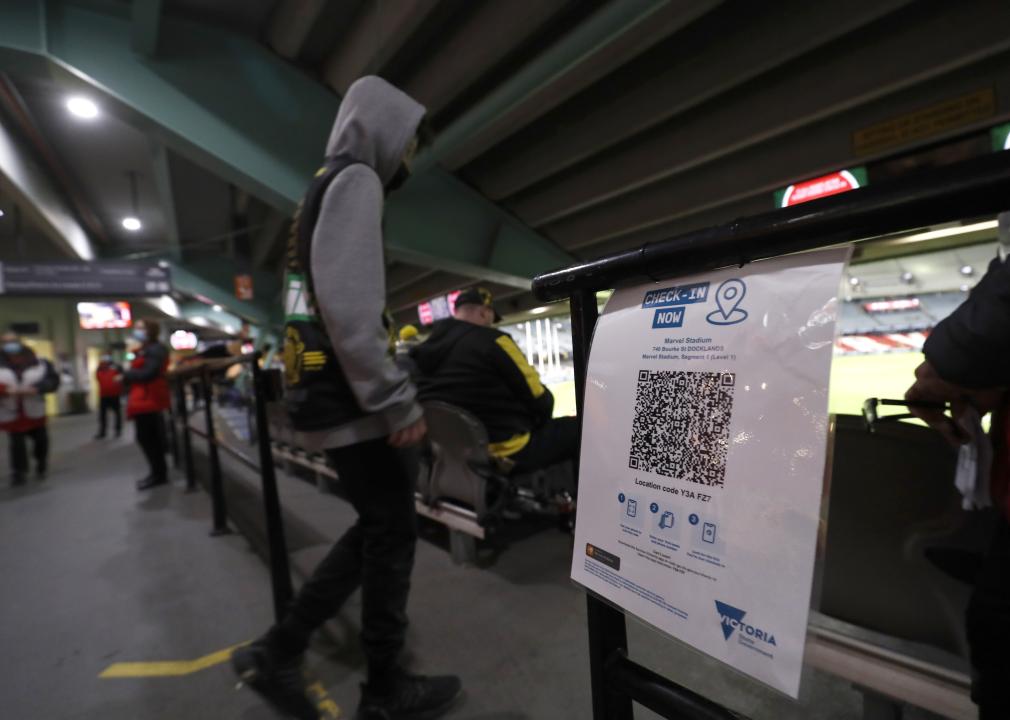

QR codes at seats

Need to remember a player’s name? Want to look up an opponent’s statistics at halftime? The team at Digital Seat Media has you covered.

Thus far, the company has added seat tags to more than 50 venues—including two NFL stadiums—with QR codes to promote more engagement with the product on the field. After scanning the code, fans can access augmented reality features, look up rosters and scores, participate in sponsorship integrations, and answer fan polls on the mobile platform.

Boris Streubel/Getty Images for DFL // Getty Images

Real-time data analytics and generative AI

As more venues look to reinvigorate the in-stadium experience, some have started using generative artificial intelligence and real-time data analytics. Though not used widely yet, generative AI tools can create new content—text, imagery, or music—in conjunction with the game, providing updates, instant replays, and location-based dining suggestions

Last year, the Masters golf tournament even began including AI score projections in its mobile app. Real-time data is streamlining various stadium pitfalls, allowing operation managers to monitor staffing issues at busy food spots, adjust parking flows, and alert custodians to dirty or damaged bathrooms. The data also helps with security measures. Open up an app at a venue like the Honda Center in Anaheim, California, and report safety issues or belligerent fans to help better target disruptions and preserve an enjoyable experience.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Uniqode and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Business

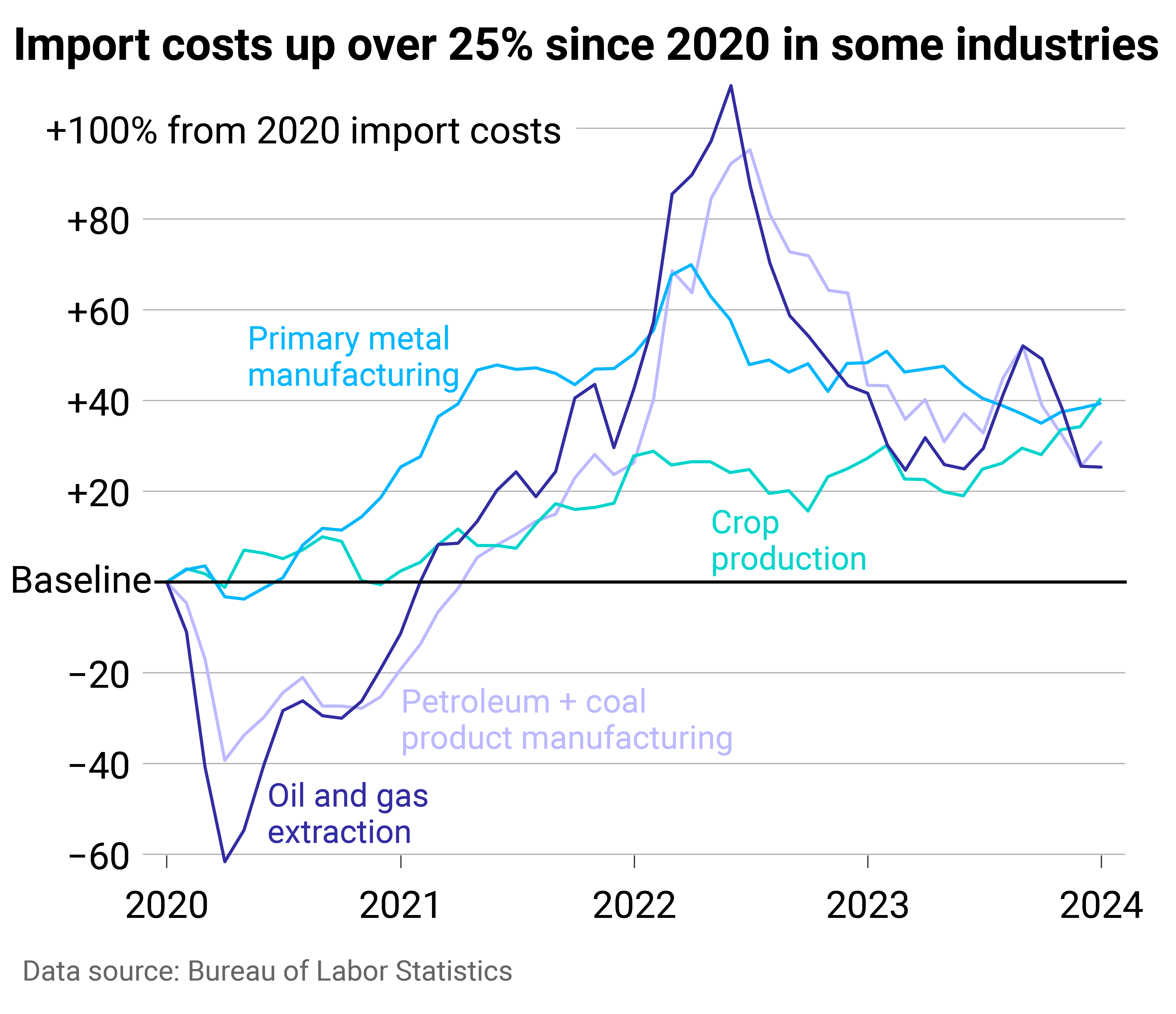

Import costs in these industries are keeping prices high

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 11, 2024

Inflation has cooled substantially, but Americans are still feeling the strain of sky-high prices. Consumers have to spend more on the same products, from the grocery store to the gas pump, than ever before.

Increased import costs are part of the problem. The U.S. is the largest goods importer in the world, bringing in $3.2 trillion in 2022. Import costs rose dramatically in 2021 and 2022 due to shipping constraints, world events, and other supply chain interruptions and cost pressures. At the June 2022 peak, import costs for all commodities were up 18.6% compared to January 2020.

While import costs have since fallen most months—helping to lower inflation—they remain nearly 12% above what they were in 2020. And beginning in 2024, import costs began to rise again, with January seeing the highest one-month increase since March 2022.

Machinery Partner used Bureau of Labor Statistics data to identify the soaring import costs that have translated to higher costs for Americans. Imports in a few industries have had an outsized impact, helping drive some of the overall spikes. Crop production, primary metal manufacturing, petroleum and coal product manufacturing, and oil and gas extraction were the worst offenders, with costs for each industry remaining at least 20% above 2020.

![]()

Machinery Partner

Imports related to crops, oil, and metals are keeping costs up

At the mid-2022 peak, import costs related to oil, gas, petroleum, and coal products had the highest increases, doubling their pre-pandemic costs. Oil prices went up globally as leaders anticipated supply disruptions from the conflict in Ukraine. The U.S. and other allied countries put limits on Russian revenues from oil sales through a price cap of oil, gas, and coal from the country, which was enacted in 2022.

This activity around the world’s second-largest oil producer pushed prices up throughout the market and intensified fluctuations in crude oil prices. Previously, the U.S. had imported hundreds of thousands of oil barrels from Russia per day, making the country a leading source of U.S. oil. In turn, the ban affected costs in the U.S. beyond what occurred in the global economy.

Americans felt this at the pump—with gasoline prices surging 60% for consumers year-over-year in June 2022 and remaining elevated to this day—but also throughout the economy, as the entire supply chain has dealt with higher gas, oil, and coal prices.

Some of the pressure from petroleum and oil has shifted to new industries: crop production and primary metal manufacturing. In each of these sectors, import costs in January were up about 40% from 2020.

Primary metal manufacturing experienced record import price growth in 2021, which continued into early 2022. The subsequent monthly and yearly drops have not been substantial enough to bring costs down to pre-COVID levels. Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting shows that increasing alumina and aluminum production prices had the most significant influence on primary metal import prices. Aluminum is widely used in consumer products, from cars and parts to canned beverages, which in turn inflated rapidly.

Aluminum was in short supply in early 2022 after high energy costs—i.e., gas—led to production cuts in Europe, driving aluminum prices to a 13-year high. The U.S. also imposes tariffs on aluminum imports, which were implemented in 2018 to cut down on overcapacity and promote U.S. aluminum production. Suppliers, including Canada, Mexico, and European Union countries, have exemptions, but the tax still adds cost to imports.

U.S. agricultural imports have expanded in recent decades, with most products coming from Canada, Mexico, the EU, and South America. Common agricultural imports include fruits and vegetables—especially those that are tropical or out-of-season—as well as nuts, coffee, spices, and beverages. Turmoil with Russia was again a large contributor to cost increases in agricultural trade, alongside extreme weather events and disruptions in the supply chain. Americans felt these price hikes directly at the grocery store.

The U.S. imports significantly more than it exports, and added costs to those imports are felt far beyond its ports. If import prices continue to rise, overall inflation would likely follow, pushing already high prices even further for American consumers.

Story editing by Shannon Luders-Manuel. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Machinery Partner and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Featured

-

Business5 months ago

Business5 months agomesh conference goes deep on AI, with experts focusing in on training, ethics, and risk

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoSkill-based hiring is the answer to labour shortages, BCG report finds

-

Events6 months ago

Events6 months agoTop 5 tech and digital transformation events to wrap up 2023

-

People4 months ago

People4 months agoHow connected technologies trim rework and boost worker safety in hands-on industries

-

Events3 months ago

Events3 months agoThe Northern Lights Technology & Innovation Forum comes to Calgary next month