Business

Evolution of the 401(k)

Published

2 years agoon

Evolution of the 401(k)

Americans held $7.3 trillion in 401(k) plans as of June 30, 2021, according to the Investment Company Institute. And the typical wealth held in an American family’s 401(k) has more than tripled since the late 1980s. With the widespread adoption of 401(k) plans, it might surprise you that they’re a relatively new employee benefit—and one that was created unintentionally by lawmakers.

Today, public and private sector employees alike use a 401(k)—or the nonprofit equivalent, a 403(b)—in order to plan for a comfortable retirement. In essence, a 401(k) allows an employee to forgo receiving a portion of their income, instead steering it into an account where the money can grow through investments. Unlike pensions, these retirement plans put more of the planning decisions—and responsibility—on employees rather than the company.

Employers can contribute to an employee’s retirement savings by matching the contributions to a 401(k) account up to an amount decided by the employer.

“The savings comes off the top, so a lot of people don’t miss their money when it’s going into their 401(k),” Ted Benna, the man long-credited for introducing the 401(k) to corporate America, told Forbes in 2021.

Whether or not that savings that “comes off the top” yields small or large returns is influenced by the employee’s age, tolerance for risk as well as market conditions over the lifetime of the account.

To illustrate how Americans’ retirement savings have evolved over the decades, Guideline compiled a timeline on the evolution of the 401(k), drawing on research from the Employee Benefit Research Institute, the Investment Company Institute, and legislative records.

![]()

Debrocke/ClassicStock // Getty Images

Pre-1978: First, there were CODAs

Before the mighty 401(k) there were Cash or Deferred Arrangements, commonly known as CODAs.

These arrangements between companies and workers allowed employees to defer some of their income and the taxes they paid on it for a period of time. CODAs were a funding mechanism for stock bonus, pension, and profit-sharing plans.

In 1974, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) was enacted, creating a governmental body that oversaw and regulated company-sponsored retirement and health care plans for workers.

ERISA temporarily halted IRS plans to severely restrict retirement plans through regulation in the early 1970s, according to the EBRI. The act created a study of employee salary reduction plans as well, which the EBRI credits for influencing the creation of the 401(k) later on in the decade.

Harold M. Lambert // Getty Images

1978: The Revenue Act of 1978

The modern 401(k) originated in earnest in 1978 with a provision in The Revenue Act of 1978 which said that employees can choose to receive a portion of income as deferred compensation, and created tax structures around it.

Section 401 was originally intended by lawmakers to limit companies creating tax-advantaged profit-sharing plans that mostly benefited executives, according to the ICI. Thanks to the interpretation of the section by businessman Ted Benna, the language evolved into the basis of the modern 401(k), as it enabled profit-sharing plans to adopt CODAs.

The law was signed by President Jimmy Carter and became effective at the turn of the decade. Regulations were then created and issued by the end of 1981.

The Revenue Act of 1978 not only created the foundation for 401(k) savings plans but also flexible spending accounts for medical expenses and the independent contractor classification as it pertains to how a company pays employment taxes.

Nicholas Hunt // Getty Images

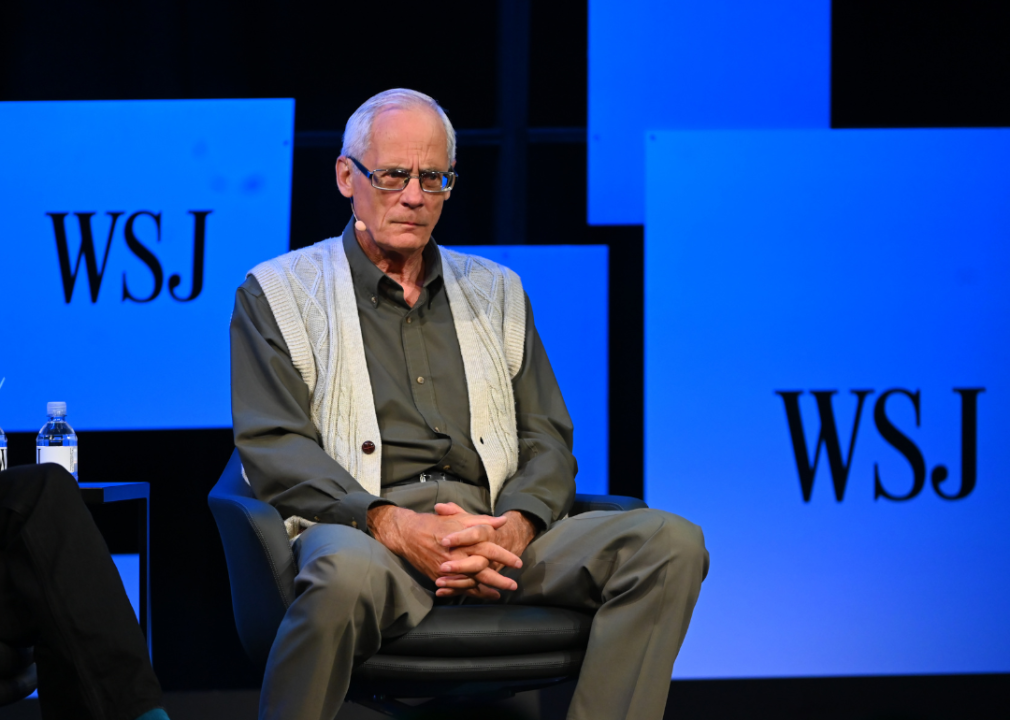

1980: “Father of the 401(k)” Ted Benna first implements the retirement plan

Ted Benna, pictured above, is popularly known as the “Father of the 401(k)” for his work advocating for companies to adopt plans in accordance with the IRS’ new Revenue Act of 1978.

His self-described “aggressive” interpretation of the eponymous 401(k) section within the Act led him to create the first-ever 401(k) savings plan in the U.S. for his consulting company.

Through business connections, Benna was introduced to Treasury officials and provided recommendations as to how 401(k) should be regulated. Ultimately, Benna was able to help steer the success and adoption of the nascent retirement tool.

Today, Benna advocates for laws that would require employers to auto-enroll their workers in 401(k) plans, meaning employers would automatically deduct payroll deferrals unless an employee elects not to participate. One of the biggest downsides to 401(k) plans is actually that more workers don’t utilize them sooner in their careers. The earlier a person starts contributing money to one of these retirement accounts, the better positioned they are to significantly grow funds by their target retirement age.

While 68% of private sector American workers had access to employee-sponsored retirement plans in 2021, only about half of all Americans took advantage of one.

Barbara Alper // Getty Images

1981: IRS clarification leads major companies to adopt 401(k) policies

In the late 1970s, pioneering aviation company Hughes Aircraft was well on its way to becoming the largest industrial employer in the state of California. The company’s outside legal consultant Ethan Lipsig was writing letters to Hughes Aircraft, encouraging the company to turn the savings plan it offered employees into a 401(k) plan.

But it wasn’t until the IRS issued regulations assuring employers that they could legally defer a portion of payroll compensation to a 401(k) savings account that companies like Hughes, J.C. Penney, Johnson & Johnson, and PepsiCo began offering the plans to workers.

Nearly half of all large employers in the U.S. were offering 401(k) plans to their workers by the end of 1982.

MPI // Getty Images

1984-1986: The Tax Reform Acts of 1984 and 1986

In 1984 and again in 1986 U.S. lawmakers, pictured above, made amendments to the country’s tax code sometimes referred to today as the “Reagan tax cuts.”

In 1984, laws were amended as part of the so-called Deficit Reduction Act to tighten the rules around deferred compensation, including 401(k) savings plans. The legislation ensured that less highly compensated employees could also benefit from plans—not just the highest paid workers. In a brief published in September 1985, the EBRI expressed concern that Reagan’s amendment could jeopardize the popularity of 401(k) savings plans.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 consolidated tax brackets, lowered federal income taxes, and placed an annual limit on deferred compensation, according to the EBRI. It had the added benefit of “endorsing” the 401(k) as a legitimate retirement vehicle because the Act implemented a 401(k)-type plan for federal employees.

David Hume Kennerly // Getty Images

1996: The Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996

The Small Business Job Protection Act came along in 1996 and simplified retirement programs—called SIMPLE plans—for small businesses. The act signed into law by President Bill Clinton was intended to help make America’s small businesses more competitive with large firms.

It specifically made the employer-matching contribution process easier through SIMPLE plans for businesses with fewer than 100 employees. The act also lowered taxes for small businesses, created safe-harbor formulas to eliminate the need for nondiscrimination testing, simplified pensions, and raised the minimum wage.

Mark Wilson // Getty Images

2001: The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act

The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act paved the way for many changes including allowing catch-up contributions for employees aged 50 and older, requiring faster vesting timeframes for matching contributions, and, perhaps most notably, introducing the Roth 401(k).

Officially launched to the public in 2006, a Roth 401(k) is employer-sponsored like a traditional 401(k). The account holder elects to contribute a portion of their income to the account, and the employer has the option to contribute matching funds.

The difference is that contributions are taxed before they go into the Roth account, which means that the owner doesn’t have to pay taxes again when they withdraw from the account after they are aged 59 and a half or older. At its core, the Roth 401(k) gives the owner the advantage of paying taxes now instead of being taxed on withdrawals later in life when the account is worth more monetarily—or when future tax rates may have increased.

Millennials are more likely to contribute to Roth 401(k)s than older generations, according to a 2019 report from the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies.

Tom Williams // Getty Images

2022: The Securing a Strong Retirement Act is making its way through Congress

Flash forward to the current day and much has changed about planning for retirement. Pensions have all but disappeared and many Americans continue to redefine what retirement will look like for them — and how to plan ahead for it. In the U.S., people live on average 10 years longer today than they did when the 401(k) was created in 1978, and recent research suggests that generations younger than baby boomers may live longer than their retirement accounts will support them. So it’s more important than ever that people stay on top of changes in their retirement planning. As more tools, technology, and resources became available for learning and investing, legislation has also been introduced to help Americans navigate retirement decisions.

The Senate is currently debating a set of bills collectively referred to as “SECURE 2.0,” as they build on the SECURE Act passed in 2019. Among other changes, the 2019 legislation made it so part-time workers could participate in retirement plans and made offering plans more appealing for small businesses that may have been hesitant in the past.

SECURE 2.0 goes further to make employee enrollment in a retirement savings plan like a 401(k) mandatory. It would also alter rules around making late contributions to payments so that Americans older than 50 can contribute even more than previously to their accounts.

This story originally appeared on Guideline and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

You may like

Business

Import costs in these industries are keeping prices high

Published

1 week agoon

April 11, 2024

Inflation has cooled substantially, but Americans are still feeling the strain of sky-high prices. Consumers have to spend more on the same products, from the grocery store to the gas pump, than ever before.

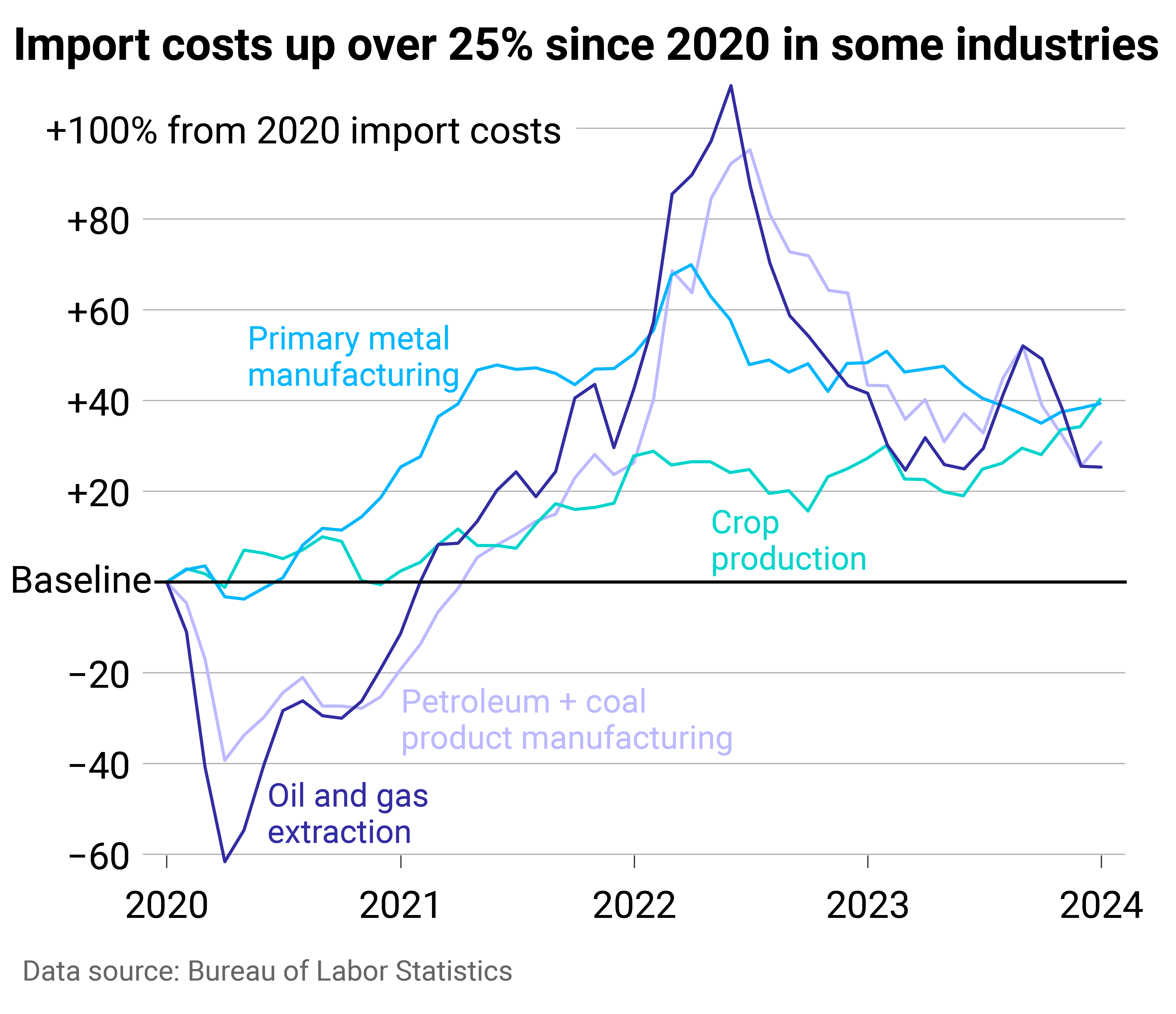

Increased import costs are part of the problem. The U.S. is the largest goods importer in the world, bringing in $3.2 trillion in 2022. Import costs rose dramatically in 2021 and 2022 due to shipping constraints, world events, and other supply chain interruptions and cost pressures. At the June 2022 peak, import costs for all commodities were up 18.6% compared to January 2020.

While import costs have since fallen most months—helping to lower inflation—they remain nearly 12% above what they were in 2020. And beginning in 2024, import costs began to rise again, with January seeing the highest one-month increase since March 2022.

Machinery Partner used Bureau of Labor Statistics data to identify the soaring import costs that have translated to higher costs for Americans. Imports in a few industries have had an outsized impact, helping drive some of the overall spikes. Crop production, primary metal manufacturing, petroleum and coal product manufacturing, and oil and gas extraction were the worst offenders, with costs for each industry remaining at least 20% above 2020.

![]()

Machinery Partner

Imports related to crops, oil, and metals are keeping costs up

At the mid-2022 peak, import costs related to oil, gas, petroleum, and coal products had the highest increases, doubling their pre-pandemic costs. Oil prices went up globally as leaders anticipated supply disruptions from the conflict in Ukraine. The U.S. and other allied countries put limits on Russian revenues from oil sales through a price cap of oil, gas, and coal from the country, which was enacted in 2022.

This activity around the world’s second-largest oil producer pushed prices up throughout the market and intensified fluctuations in crude oil prices. Previously, the U.S. had imported hundreds of thousands of oil barrels from Russia per day, making the country a leading source of U.S. oil. In turn, the ban affected costs in the U.S. beyond what occurred in the global economy.

Americans felt this at the pump—with gasoline prices surging 60% for consumers year-over-year in June 2022 and remaining elevated to this day—but also throughout the economy, as the entire supply chain has dealt with higher gas, oil, and coal prices.

Some of the pressure from petroleum and oil has shifted to new industries: crop production and primary metal manufacturing. In each of these sectors, import costs in January were up about 40% from 2020.

Primary metal manufacturing experienced record import price growth in 2021, which continued into early 2022. The subsequent monthly and yearly drops have not been substantial enough to bring costs down to pre-COVID levels. Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting shows that increasing alumina and aluminum production prices had the most significant influence on primary metal import prices. Aluminum is widely used in consumer products, from cars and parts to canned beverages, which in turn inflated rapidly.

Aluminum was in short supply in early 2022 after high energy costs—i.e., gas—led to production cuts in Europe, driving aluminum prices to a 13-year high. The U.S. also imposes tariffs on aluminum imports, which were implemented in 2018 to cut down on overcapacity and promote U.S. aluminum production. Suppliers, including Canada, Mexico, and European Union countries, have exemptions, but the tax still adds cost to imports.

U.S. agricultural imports have expanded in recent decades, with most products coming from Canada, Mexico, the EU, and South America. Common agricultural imports include fruits and vegetables—especially those that are tropical or out-of-season—as well as nuts, coffee, spices, and beverages. Turmoil with Russia was again a large contributor to cost increases in agricultural trade, alongside extreme weather events and disruptions in the supply chain. Americans felt these price hikes directly at the grocery store.

The U.S. imports significantly more than it exports, and added costs to those imports are felt far beyond its ports. If import prices continue to rise, overall inflation would likely follow, pushing already high prices even further for American consumers.

Story editing by Shannon Luders-Manuel. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Machinery Partner and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Business

The states where people pay the most in car insurance premiums

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 4, 2024

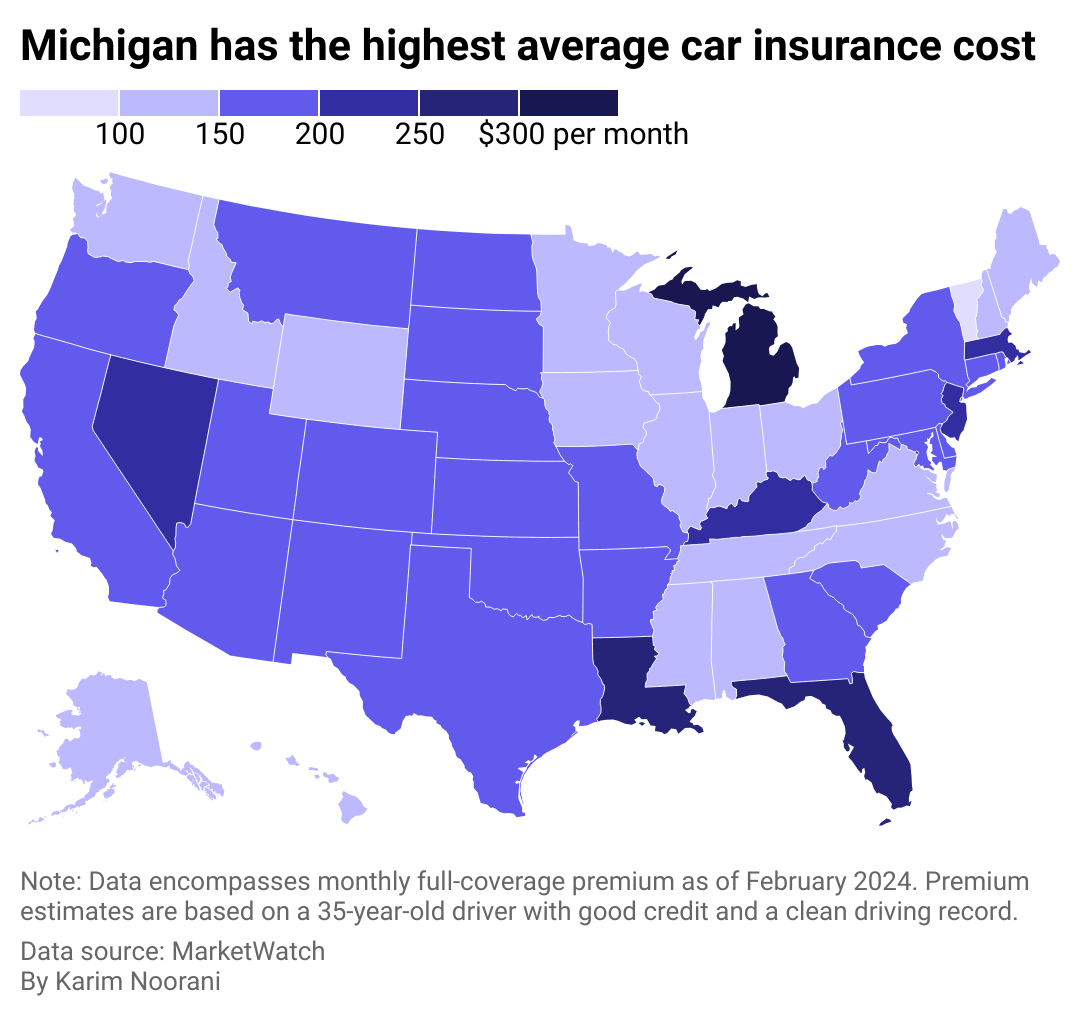

Nearly every state requires drivers to carry car insurance, but the laws vary, and many factors affect the cost of coverage.

Some are controllable, at least to degrees: the type of car you have and your credit history. Some are not: your age and gender. Your marital status, place of residence, and claims history are among the other variables that go into it.

Across the United States, premiums are soaring, rising 20% year over year and increasing six times faster than consumer prices overall as of December 2023, CBS reported. Last September, CNN noted that car insurance rates jumped more in the previous year than they had since 1976.

CBS pointed to many potential reasons for these increases in prices. Coronavirus pandemic-era issues have made buying, fixing, and replacing vehicles costlier. Extreme weather events caused by climate change also damage more vehicles, while insurance companies are increasing their business costs. Severe and more frequent crashes are to blame as well, CNN reported.

On top of these, local factors such as population density, the number of uninsured drivers, and the frequency of insurance claims all affect premiums, which can lead motorists to change or switch their coverage, use other modes of transportation, or even alter decisions about when to buy a vehicle or what to look for.

To see how geography affects cost, Cheap Insurance mapped the states where people pay the most in car insurance premiums using MarketWatch data. Premium estimates were based on full-coverage car insurance for a 35-year-old driver with good credit and a clean driving record. Data accurate as of February 2024.

![]()

Cheap Insurance

Americans pay $167 per month on average for full-coverage insurance

There are common denominators among the five states where it’s most expensive to have car insurance: Michigan, Florida, Louisiana, Nevada, and Kentucky. Washington D.C. is another pricey locale, ranking #4 overall.

Three of these six are no-fault jurisdictions and require additional coverage beyond coverage to pay for medical costs. Michigan notably calls for $250,000 in personal injury protection (though people with Medicaid and Medicare may qualify for lower limits), $1 million in personal property insurance for damage done by your car in Michigan, and residual bodily injury and property damage liability that starts at $250,000 for a person harmed in an accident.

Other commonalities between these states include high urban population densities. At least 9 in 10 people in Nevada, Florida, and Washington D.C. live in cities and urban areas, which leads to more crashes and thefts and high rates of uninsured drivers and lawsuits. Additionally, Louisiana, Florida, and Kentucky rank #5, #8, and #10, respectively, in motor vehicle crash deaths per 100 million vehicle miles traveled in 2021 based on Department of Transportation data analyzed by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

Canva

#5. Kentucky

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $210

– Monthly liability insurance: $57

Canva

#4. Nevada

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $232

– Monthly liability insurance: $107

Canva

#3. Louisiana

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $253

– Monthly liability insurance: $77

Canva

#2. Florida

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $270

– Monthly liability insurance: $115

Canva

#1. Michigan

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $304

– Monthly liability insurance: $113

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Cheap Insurance and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Business

How businesses can protect themselves from the rising threat of deepfakes

Dive into the world of deepfakes and explore the risks, strategies and insights to fortify your organization’s defences

Published

1 month agoon

March 11, 2024By

Dave Gordon

In Billy Joel’s latest video for the just-released song Turn the Lights Back On, it features him in several deepfakes, singing the tune as himself, but decades younger. The technology has advanced to the extent that it’s difficult to distinguish between that of a fake 30-year-old Joel, and the real 75-year-old today.

This is where tech is being used for good. But when it’s used with bad intent, it can spell disaster. In mid-February, a report showed a clerk at a Hong Kong multinational who was hoodwinked by a deepfake impersonating senior executives in a video, resulting in a $35 million theft.

Deepfake technology, a form of artificial intelligence (AI), is capable of creating highly realistic fake videos, images, or audio recordings. In just a few years, these digital manipulations have become so sophisticated that they can convincingly depict people saying or doing things that they never actually did. In little time, the tech will become readily available to the layperson, who’ll require few programming skills.

Legislators are taking note

In the US, the Federal Trade Commission proposed a ban on those who impersonate others using deepfakes — the greatest concern being how it can be used to fool consumers. The Feb. 16 ban further noted that an increasing number of complaints have been filed from “impersonation-based fraud.”

A Financial Post article outlined that Ontario’s information and privacy commissioner, Patricia Kosseim, says she feels “a sense of urgency” to act on artificial intelligence as the technology improves. “Malicious actors have found ways to synthetically mimic executive’s voices down to their exact tone and accent, duping employees into thinking their boss is asking them to transfer funds to a perpetrator’s account,” the report said. Ontario’s Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence Framework, for which she consults, aims to set guides on the public sector use of AI.

In a recent Microsoft blog, the company stated their plan is to work with the tech industry and government to foster a safer digital ecosystem and tackle the challenges posed by AI abuse collectively. The company also said it’s already taking preventative steps, such as “ongoing red team analysis, preemptive classifiers, the blocking of abusive prompts, automated testing, and rapid bans of users who abuse the system” as well as using watermarks and metadata.

That prevention will also include enhancing public understanding of the risks associated with deepfakes and how to distinguish between legitimate and manipulated content.

Cybercriminals are also using deepfakes to apply for remote jobs. The scam starts by posting fake job listings to collect information from the candidates, then uses deepfake video technology during remote interviews to steal data or unleash ransomware. More than 16,000 people reported that they were victims of this scam to the FBI in 2020. In the US, this kind of fraud has resulted in a loss of more than $3 billion USD. Where possible, they recommend job interviews should be in person to avoid these threats.

Catching fakes in the workplace

There are detector programs, but they’re not flawless.

When engineers at the Canadian company Dessa first tested a deepfake detector that was built using Google’s synthetic videos, they found it failed more than 40% of the time. The Seattle Times noted that the problem in question was eventually fixed, and it comes down to the fact that “a detector is only as good as the data used to train it.” But, because the tech is advancing so rapidly, detection will require constant reinvention.

There are other detection services, often tracing blood flow in the face, or errant eye movements, but these might lose steam once the hackers figure out what sends up red flags.

“As deepfake technology becomes more widespread and accessible, it will become increasingly difficult to trust the authenticity of digital content,” noted Javed Khan, owner of Ontario-based marketing firm EMpression. He said a focus of the business is to monitor upcoming trends in tech and share the ideas in a simple way to entrepreneurs and small business owners.

To preempt deepfake problems in the workplace, he recommended regular training sessions for employees. A good starting point, he said, would be to test them on MIT’s eight ways the layperson can try to discern a deepfake on their own, ranging from unusual blinking, smooth skin, and lighting.

Businesses should proactively communicate through newsletters, social media posts, industry forums, and workshops, about the risks associated with deepfake manipulation, he told DX Journal, to “stay updated on emerging threats and best practices.”

To keep ahead of any possible attacks, he said companies should establish protocols for “responding swiftly” to potential deepfake attacks, including issuing public statements or corrective actions.

How can a deepfake attack impact business?

The potential to malign a company’s reputation with a single deepfake should not be underestimated.

“Deepfakes could be racist. It could be sexist. It doesn’t matter — by the time it gets known that it’s fake, the damage could be already done. And this is the problem,” said Alan Smithson, co-founder of Mississauga-based MetaVRse and investor at Your Director AI.

“Building a brand is hard, and then it can be destroyed in a second,” Smithson told DX Journal. “The technology is getting so good, so cheap, so fast, that the power of this is in everybody’s hands now.”

One of the possible solutions is for businesses to have a code word when communicating over video as a way to determine who’s real and who’s not. But Smithson cautioned that the word shouldn’t be shared around cell phones or computers because “we don’t know what devices are listening to us.”

He said governments and companies will need to employ blockchain or watermarks to identify fraudulent messages. “Otherwise, this is gonna get crazy,” he added, noting that Sora — the new AI text to video program — is “mind-blowingly good” and in another two years could be “indistinguishable from anything we create as humans.”

“Maybe the governments will step in and punish them harshly enough that it will just be so unreasonable to use these technologies for bad,” he continued. And yet, he lamented that many foreign actors in enemy countries would not be deterred by one country’s law. It’s one downside he said will always be a sticking point.

It would appear that for now, two defence mechanisms are the saving grace to the growing threat posed by deepfakes: legal and regulatory responses, and continuous vigilance and adaptation to mitigate risks. The question remains, however, whether safety will keep up with the speed of innovation.

Dave is a journalist whose work has appeared in more than 100 media outlets around the world, including BBC, National Post, Washington Times, Globe and Mail, New York Times, Baltimore Sun.

Featured

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agomesh conference goes deep on AI, with experts focusing in on training, ethics, and risk

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoSkill-based hiring is the answer to labour shortages, BCG report finds

-

Events6 months ago

Events6 months agoTop 5 tech and digital transformation events to wrap up 2023

-

People4 months ago

People4 months agoHow connected technologies trim rework and boost worker safety in hands-on industries

-

Events3 months ago

Events3 months agoThe Northern Lights Technology & Innovation Forum comes to Calgary next month