Business

The industries where workers are quitting their jobs in droves

Published

1 year agoon

Much has been made of the Great Resignation—the mass exodus of American workers from their jobs since COVID-19 hit. Although the pandemic was initially characterized by mass layoffs, those who kept their jobs began examining the role of work in their lives as COVID endured.

Working people noticed they were burning out trying to juggle work and family responsibilities as never before. Many came to realize they were being underpaid and unfairly treated, leaving their jobs in search of better conditions or opting out of the workforce entirely. That trend shows no sign of slowing down, although not all industries have been affected evenly.

Stacker used preliminary October 2022 Bureau of Labor Statistics data to rank the 17 major employment sectors by their quit rates, which BLS calculates as the number of quits during the month as a percentage of total employment. The analysis also includes the number of people who quit in that industry and the quit rate change from October 2021.

The overall quit rate for October 2022 was 2.6%, with more than 4 million U.S. workers quitting their jobs. That rate is about the same, if not slightly down, compared to the previous year. Of the 17 industries represented on this list, five saw an increase in the overall quit rate in late 2022 compared to the previous year. For example, while circumstances may have caused about 58,000 musicians and entertainers to quit in May 2021, the level went up to 80,000 by October 2022.

Find out which industries have workers quitting their jobs in droves below.

You may also like: This is what really happens to retail food waste

![]()

fizkes // Shutterstock

#17. Federal government

– October 2022 quit rate: 0.7% (-0.2 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 20,000

A higher number of federal workers than usual are leaving their jobs—and surveys of these workers say several factors are at play. One is the typically low pay for most government work. But workers cite other factors influencing their decision to quit as well—among them a perceived lack of respect at work, in addition to lack of opportunities for advancement.

Amnaj Khetsamtip // Shutterstock

#16. Information

– October 2022 quit rate: 0.9% (-1.1 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 28,000

Many information workers have been quitting their jobs since the pandemic began. Some of them are no doubt in the movie and publishing industries, which had to shift rapidly to adapt to restrictions on group gatherings. And many IT professionals were allowed to work remotely during the pandemic, and either changed jobs to take advantage of newly available opportunities, or decided to avoid requirements to return to in-person work by finding new employers.

Monkey Business Images // Shutterstock

#15. State and local education

– October 2022 quit rate: 1.0% (No change)

– October 2022 quit count: 107,000

Many teachers and other school workers are leaving their posts. The pandemic vastly changed the experience of teaching in schools, thanks to the challenges of teaching over Zoom and pressure from large numbers of people out on sick leave, as well as intermittent school closings. More than half of public school teachers are considering leaving teaching due to burnout from these pandemic-wrought challenges, according to a February 2022 report from NBC News.

Jacob Lund // Shutterstock

#14. State and local government

– October 2022 quit rate: 1.2% (-0.1 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 108,000

Just as with federal employees, state and local government workers are also leaving their jobs in droves, with many of them reporting they are under-compensated compared to the local labor market. To these workers, this reality is harmful to their family’s financial health. In one survey, 1 in 3 public sector employees report that they would have difficulty paying an unexpected $400 bill in an emergency.

Drazen Zigic // Shutterstock

#13. Educational services

– October 2022 quit rate: 1.4% (-0.1 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 52,000

Private-sector education workers, those who work at private schools, technical institutes, and universities, are quitting their jobs for many of the same reasons that those in public school systems are: The changes wrought by the pandemic have contributed to significant burnout and dissatisfaction. And many teachers are finding their skills valued by corporations, who are hiring former teachers, often with significantly boosted pay.

You may also like: The cost of gasoline the year you started driving

GaudiLab // Shutterstock

#12. Finance and insurance

– October 2022 quit rate: 1.5% (+0.4 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 99,000

Although finance and insurance roles are typically well compensated, workers in these industries are quitting in search of a better quality of life, such as shorter work hours. “People [in finance and insurance] are evaluating the role of work in their lives differently,” Qualtrics chief workplace psychologist Ben Granger told Fortune.

ESB Professional // Shutterstock

#11. Wholesale trade

– October 2022 quit rate: 1.7% (-0.3 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 101,000

Not only are workers quitting wholesale trade, but the companies that employ them are having a hard time filling these vacant roles. One potential reason? Significant supply chain delays, thanks to geopolitical instability and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mark Agnor // Shutterstock

#9. Mining and logging (tie)

– October 2022 quit rate: 2.1% (+0.2 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 13,000

The U.S. Energy Information Administration says lack of demand is the reason that coal production is down. Mining outposts shared shutdowns with logging companies, which weren’t selling much lumber and couldn’t find enough truckers either. However, the pendulum swung back and lumber companies raised production and costs in response to increasing demand—though that may shift again as the housing market cools.

Firma V // Shutterstock

#9. Manufacturing (tie)

– October 2022 quit rate: 2.1% (-0.3 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 268,000

Pressure to raise wages is increasing, especially in the manufacturing industry. While some factories are meeting the moment with better wage and benefit packages for their employees, others are watching their workers leave for greener pastures.

wavebreakmedia // Shutterstock

#8. Real estate and rental and leasing

– October 2022 quit rate: 2.3% (+0.3 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 54,000

When eviction moratoriums became a nationwide standard during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, property managers were hurt by the substantial loss in rental earnings. A lack of new tenants and a lack of income makes this job difficult to keep, especially as renters try to regain their financial footing following the economic downturn. Workers whose jobs are connected to home purchases and sales may also be seeking other work as mortgage interest rates climb.

You may also like: Do you know the brands behind these famous slogans?

Emre Ucarer // Shutterstock

#7. Construction

– October 2022 quit rate: 2.4% (-0.1 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 189,000

Material costs increased for construction companies, a direct connection to the hardships experienced by the mining and lumber industries. This cost increase resulted in major job losses during the pandemic, and now the construction industry is turning to President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for relief at the federal level.

Rawpixel.com // Shutterstock

#6. Health care and social assistance

– October 2022 quit rate: 2.5% (-0.1 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 515,000

There are many issues surrounding the mass exodus of health care workers: the debate on requiring vaccinations for health care professionals and their patients, the extreme burnout from caring for COVID-19 patients, and the trauma of watching patients die from the virus.

Many nurses have already left the field, and a November 2022 survey found that half of remaining nurses are considering quitting their jobs.

MikeDotta // Shutterstock

#5. Transportation, warehousing, and utilities

– October 2022 quit rate: 2.8% (+0.4 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 197,000

Public transportation authorities were strapped for resources when the pandemic hit, needing to implement new cleaning and scheduling strategies as well as planning to regain future riders. Meanwhile, supply chain troubles held up warehousing, trucking, and rail shipping work.

Monkey Business Images // Shutterstock

#4. Professional and business services

– October 2022 quit rate: 2.9% (-0.4 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 655,000

This sector is broad, spanning managerial, technical, administrative, and even waste management services for businesses. It’s an industry that carries a lot of weight, but managing a company is difficult, as evidenced by how many businesses have struggled in the past couple of years.

Anna Jurkovska // Shutterstock

#3. Arts, entertainment, and recreation

– October 2022 quit rate: 3.4% (+0.1 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 80,000

Every concert and entertainment venue from Broadway to the House of Blues was temporarily closed in early 2020, so many musicians, actors, and entertainers had to quickly move on to other industries to maintain their usual income. While customer demand for events is climbing again, workers are still looking for more stability.

You may also like: Youngest billionaires in America

Aleksandar Malivuk // Shutterstock

#2. Retail trade

– October 2022 quit rate: 3.8% (-0.6 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 606,000

Retail jobs are notorious for poor working conditions and low wages, and reports say that the pandemic only worsened the problem. Employees at grocery stores and pet stores were placed on the front lines without hazard pay, even when all other industries closed. Workers are wary of returning, with social media and news reports highlighting demanding customers treating retail employees poorly.

wavebreakmedia // Shutterstock

#1. Accommodation and food services

– October 2022 quit rate: 5.8% (-0.1 percentage points since 2021)

– October 2022 quit count: 789,000

Food service workers were not exempt from the hardships experienced by retail workers. Many minimum wage jobs like these didn’t transition well, leading workers to expect more pay to offset the increased hazards of their workplace. Companies are responding, but slowly, as their other costs also rise.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

You may like

Business

5 tech advancements sports venues have added since your last event

Published

1 day agoon

April 19, 2024

In today’s digital climate, consuming sports has never been easier. Thanks to a plethora of streaming sites, alternative broadcasts, and advancements to home entertainment systems, the average fan has myriad options to watch and learn about their favorite teams at the touch of a button—all without ever having to leave the couch.

As a result, more and more sports venues have committed to improving and modernizing their facilities and fan experiences to compete with at-home audiences. Consider using mobile ticketing and parking passes, self-service kiosks for entry and ordering food, enhanced video boards, and jumbotrons that supply data analytics and high-definition replays. These innovations and upgrades are meant to draw more revenue and attract various sponsored partners. They also deliver unique and convenient in-person experiences that rival and outmatch traditional ways of enjoying games.

In Los Angeles, the Rams and Chargers’ SoFi Stadium has become the gold standard for football venues. It’s an architectural wonder with closer views, enhanced hospitality, and a translucent roof that cools the stadium’s internal temperature.

The Texas Rangers’ ballpark, Globe Life Field, added field-level suites and lounges that resemble the look and feel of a sports bar. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Clippers are building a new arena (in addition to retail space, team offices, and an outdoor public plaza) that will seat 18,000 people and feature a fan section called The Wall, which will regulate attire and rooting interest.

It’s no longer acceptable to operate with old-school facilities and technology. Just look at Commanders Field (formerly FedExField), home of the Washington Commanders, which has faced criticism for its faulty barriers, leaking ceilings, poor food options, and long lines. Understandably, the team has been attempting to find a new location to build a state-of-the-art stadium and keep up with the demand for high-end amenities.

As more organizations audit their stadiums and arenas and keep up with technological innovations, Uniqode compiled a list of the latest tech advancements to coax—and keep—fans inside venues.

![]()

Jeff Gritchen/MediaNews Group/Orange County Register // Getty Images

Just Walk Out technology

After successfully installing its first cashierless grocery store in 2020, Amazon has continued to put its tracking technology into practice.

In 2023, the Seahawks incorporated Just Walk Out technology at various merchandise stores throughout Lumen Field, allowing fans to purchase items with a swipe and scan of their palms.

The radio-frequency identification system, which involves overhead cameras and computer vision, is a substitute for cashiers and eliminates long lines.

RFID is now found in a handful of stadiums and arenas nationwide. These stores have already curbed checkout wait times, eliminated theft, and freed up workers to assist shoppers, according to Jon Jenkins, vice president of Just Walk Out tech.

Billie Weiss/Boston Red Sox // Getty Images

Self-serve kiosks

In the same vein as Amazon’s self-scanning technology, self-serve kiosks have become a more integrated part of professional stadiums and arenas over the last few years. Some of these function as top-tier vending machines with canned beers and nonalcoholic drinks, shuffling lines quicker with virtual bartenders capable of spinning cocktails and mixed drinks.

The kiosks extend past beverages, as many college and professional venues have started using them to scan printed and digital tickets for more efficient entrance. It’s an effort to cut down lines and limit the more tedious aspects of in-person attendance, and it’s led various competing kiosk brands to provide their specific conveniences.

Kyle Rivas // Getty Images

Mobile ordering

Is there anything worse than navigating the concourse for food and alcohol and subsequently missing a go-ahead home run, clutch double play, or diving catch?

Within the last few years, more stadiums have eliminated those worries thanks to contactless mobile ordering. Fans can select food and drink items online on their phones to be delivered right to their seats. Nearly half of consumers said mobile app ordering would influence them to make more restaurant purchases, according to a 2020 study at PYMNTS. Another study showed a 22% increase in order size.

Many venues, including Yankee Stadium, have taken notice and now offer personalized deliveries in certain sections and established mobile order pick-up zones throughout the ballpark.

Darrian Traynor // Getty Images

QR codes at seats

Need to remember a player’s name? Want to look up an opponent’s statistics at halftime? The team at Digital Seat Media has you covered.

Thus far, the company has added seat tags to more than 50 venues—including two NFL stadiums—with QR codes to promote more engagement with the product on the field. After scanning the code, fans can access augmented reality features, look up rosters and scores, participate in sponsorship integrations, and answer fan polls on the mobile platform.

Boris Streubel/Getty Images for DFL // Getty Images

Real-time data analytics and generative AI

As more venues look to reinvigorate the in-stadium experience, some have started using generative artificial intelligence and real-time data analytics. Though not used widely yet, generative AI tools can create new content—text, imagery, or music—in conjunction with the game, providing updates, instant replays, and location-based dining suggestions

Last year, the Masters golf tournament even began including AI score projections in its mobile app. Real-time data is streamlining various stadium pitfalls, allowing operation managers to monitor staffing issues at busy food spots, adjust parking flows, and alert custodians to dirty or damaged bathrooms. The data also helps with security measures. Open up an app at a venue like the Honda Center in Anaheim, California, and report safety issues or belligerent fans to help better target disruptions and preserve an enjoyable experience.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Uniqode and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Business

Import costs in these industries are keeping prices high

Published

1 week agoon

April 11, 2024

Inflation has cooled substantially, but Americans are still feeling the strain of sky-high prices. Consumers have to spend more on the same products, from the grocery store to the gas pump, than ever before.

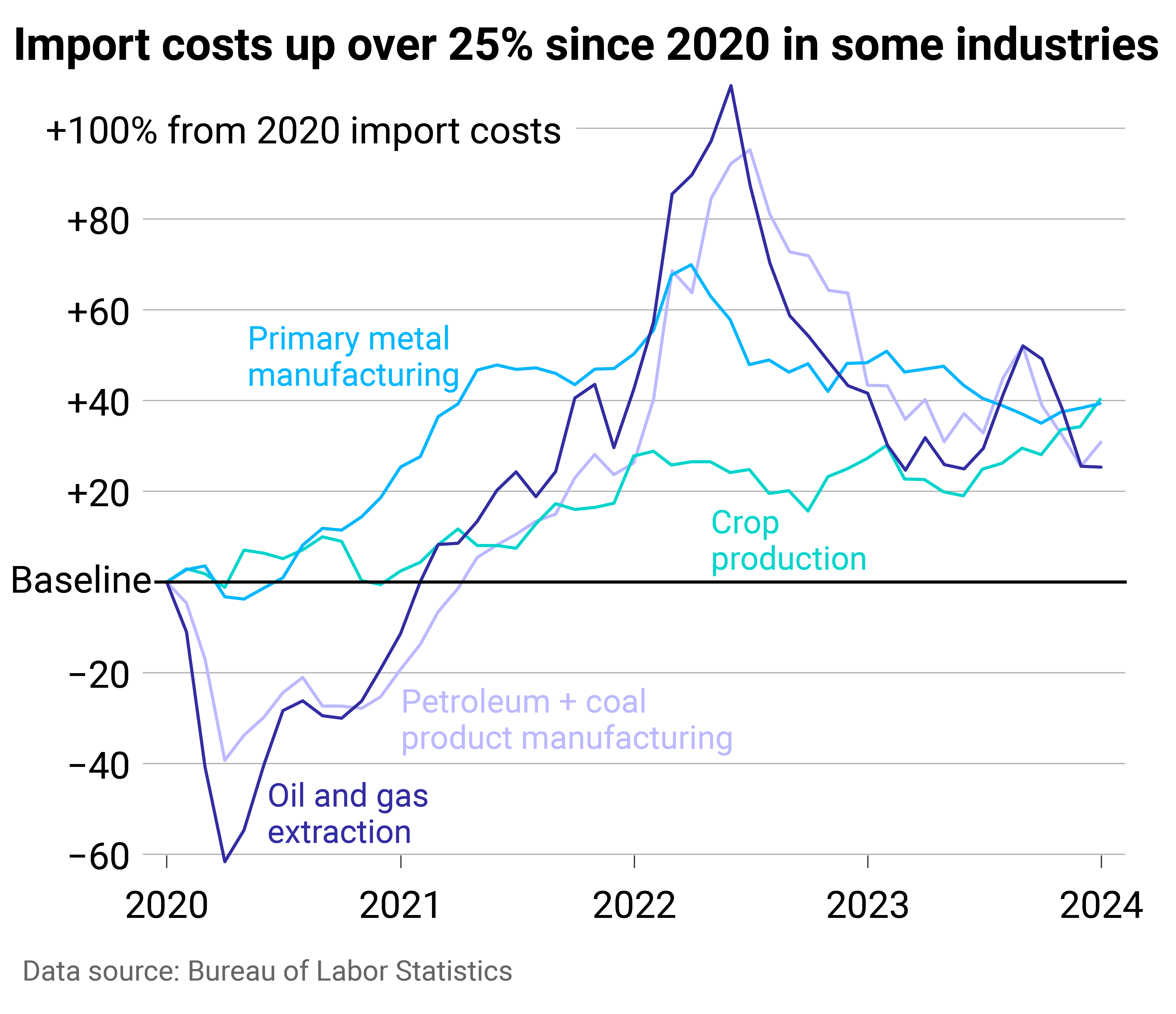

Increased import costs are part of the problem. The U.S. is the largest goods importer in the world, bringing in $3.2 trillion in 2022. Import costs rose dramatically in 2021 and 2022 due to shipping constraints, world events, and other supply chain interruptions and cost pressures. At the June 2022 peak, import costs for all commodities were up 18.6% compared to January 2020.

While import costs have since fallen most months—helping to lower inflation—they remain nearly 12% above what they were in 2020. And beginning in 2024, import costs began to rise again, with January seeing the highest one-month increase since March 2022.

Machinery Partner used Bureau of Labor Statistics data to identify the soaring import costs that have translated to higher costs for Americans. Imports in a few industries have had an outsized impact, helping drive some of the overall spikes. Crop production, primary metal manufacturing, petroleum and coal product manufacturing, and oil and gas extraction were the worst offenders, with costs for each industry remaining at least 20% above 2020.

![]()

Machinery Partner

Imports related to crops, oil, and metals are keeping costs up

At the mid-2022 peak, import costs related to oil, gas, petroleum, and coal products had the highest increases, doubling their pre-pandemic costs. Oil prices went up globally as leaders anticipated supply disruptions from the conflict in Ukraine. The U.S. and other allied countries put limits on Russian revenues from oil sales through a price cap of oil, gas, and coal from the country, which was enacted in 2022.

This activity around the world’s second-largest oil producer pushed prices up throughout the market and intensified fluctuations in crude oil prices. Previously, the U.S. had imported hundreds of thousands of oil barrels from Russia per day, making the country a leading source of U.S. oil. In turn, the ban affected costs in the U.S. beyond what occurred in the global economy.

Americans felt this at the pump—with gasoline prices surging 60% for consumers year-over-year in June 2022 and remaining elevated to this day—but also throughout the economy, as the entire supply chain has dealt with higher gas, oil, and coal prices.

Some of the pressure from petroleum and oil has shifted to new industries: crop production and primary metal manufacturing. In each of these sectors, import costs in January were up about 40% from 2020.

Primary metal manufacturing experienced record import price growth in 2021, which continued into early 2022. The subsequent monthly and yearly drops have not been substantial enough to bring costs down to pre-COVID levels. Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting shows that increasing alumina and aluminum production prices had the most significant influence on primary metal import prices. Aluminum is widely used in consumer products, from cars and parts to canned beverages, which in turn inflated rapidly.

Aluminum was in short supply in early 2022 after high energy costs—i.e., gas—led to production cuts in Europe, driving aluminum prices to a 13-year high. The U.S. also imposes tariffs on aluminum imports, which were implemented in 2018 to cut down on overcapacity and promote U.S. aluminum production. Suppliers, including Canada, Mexico, and European Union countries, have exemptions, but the tax still adds cost to imports.

U.S. agricultural imports have expanded in recent decades, with most products coming from Canada, Mexico, the EU, and South America. Common agricultural imports include fruits and vegetables—especially those that are tropical or out-of-season—as well as nuts, coffee, spices, and beverages. Turmoil with Russia was again a large contributor to cost increases in agricultural trade, alongside extreme weather events and disruptions in the supply chain. Americans felt these price hikes directly at the grocery store.

The U.S. imports significantly more than it exports, and added costs to those imports are felt far beyond its ports. If import prices continue to rise, overall inflation would likely follow, pushing already high prices even further for American consumers.

Story editing by Shannon Luders-Manuel. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Machinery Partner and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Business

The states where people pay the most in car insurance premiums

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 4, 2024

Nearly every state requires drivers to carry car insurance, but the laws vary, and many factors affect the cost of coverage.

Some are controllable, at least to degrees: the type of car you have and your credit history. Some are not: your age and gender. Your marital status, place of residence, and claims history are among the other variables that go into it.

Across the United States, premiums are soaring, rising 20% year over year and increasing six times faster than consumer prices overall as of December 2023, CBS reported. Last September, CNN noted that car insurance rates jumped more in the previous year than they had since 1976.

CBS pointed to many potential reasons for these increases in prices. Coronavirus pandemic-era issues have made buying, fixing, and replacing vehicles costlier. Extreme weather events caused by climate change also damage more vehicles, while insurance companies are increasing their business costs. Severe and more frequent crashes are to blame as well, CNN reported.

On top of these, local factors such as population density, the number of uninsured drivers, and the frequency of insurance claims all affect premiums, which can lead motorists to change or switch their coverage, use other modes of transportation, or even alter decisions about when to buy a vehicle or what to look for.

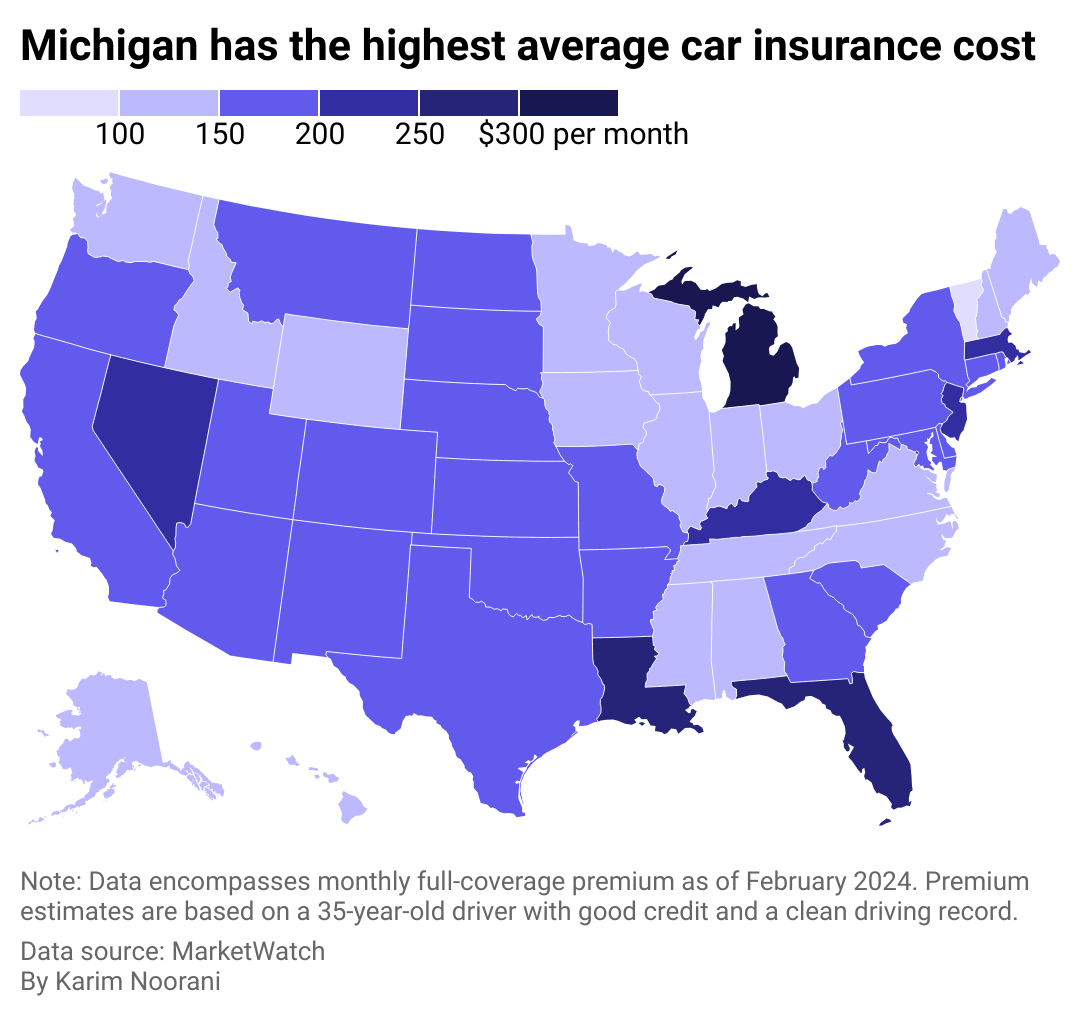

To see how geography affects cost, Cheap Insurance mapped the states where people pay the most in car insurance premiums using MarketWatch data. Premium estimates were based on full-coverage car insurance for a 35-year-old driver with good credit and a clean driving record. Data accurate as of February 2024.

![]()

Cheap Insurance

Americans pay $167 per month on average for full-coverage insurance

There are common denominators among the five states where it’s most expensive to have car insurance: Michigan, Florida, Louisiana, Nevada, and Kentucky. Washington D.C. is another pricey locale, ranking #4 overall.

Three of these six are no-fault jurisdictions and require additional coverage beyond coverage to pay for medical costs. Michigan notably calls for $250,000 in personal injury protection (though people with Medicaid and Medicare may qualify for lower limits), $1 million in personal property insurance for damage done by your car in Michigan, and residual bodily injury and property damage liability that starts at $250,000 for a person harmed in an accident.

Other commonalities between these states include high urban population densities. At least 9 in 10 people in Nevada, Florida, and Washington D.C. live in cities and urban areas, which leads to more crashes and thefts and high rates of uninsured drivers and lawsuits. Additionally, Louisiana, Florida, and Kentucky rank #5, #8, and #10, respectively, in motor vehicle crash deaths per 100 million vehicle miles traveled in 2021 based on Department of Transportation data analyzed by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

Canva

#5. Kentucky

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $210

– Monthly liability insurance: $57

Canva

#4. Nevada

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $232

– Monthly liability insurance: $107

Canva

#3. Louisiana

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $253

– Monthly liability insurance: $77

Canva

#2. Florida

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $270

– Monthly liability insurance: $115

Canva

#1. Michigan

– Monthly full-coverage insurance: $304

– Monthly liability insurance: $113

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Cheap Insurance and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Featured

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agomesh conference goes deep on AI, with experts focusing in on training, ethics, and risk

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoSkill-based hiring is the answer to labour shortages, BCG report finds

-

Events6 months ago

Events6 months agoTop 5 tech and digital transformation events to wrap up 2023

-

People4 months ago

People4 months agoHow connected technologies trim rework and boost worker safety in hands-on industries

-

Events3 months ago

Events3 months agoThe Northern Lights Technology & Innovation Forum comes to Calgary next month