Business

Evolution of the 401(k)

Published

2 years agoon

Evolution of the 401(k)

Americans held $7.3 trillion in 401(k) plans as of June 30, 2021, according to the Investment Company Institute. And the typical wealth held in an American family’s 401(k) has more than tripled since the late 1980s. With the widespread adoption of 401(k) plans, it might surprise you that they’re a relatively new employee benefit—and one that was created unintentionally by lawmakers.

Today, public and private sector employees alike use a 401(k)—or the nonprofit equivalent, a 403(b)—in order to plan for a comfortable retirement. In essence, a 401(k) allows an employee to forgo receiving a portion of their income, instead steering it into an account where the money can grow through investments. Unlike pensions, these retirement plans put more of the planning decisions—and responsibility—on employees rather than the company.

Employers can contribute to an employee’s retirement savings by matching the contributions to a 401(k) account up to an amount decided by the employer.

“The savings comes off the top, so a lot of people don’t miss their money when it’s going into their 401(k),” Ted Benna, the man long-credited for introducing the 401(k) to corporate America, told Forbes in 2021.

Whether or not that savings that “comes off the top” yields small or large returns is influenced by the employee’s age, tolerance for risk as well as market conditions over the lifetime of the account.

To illustrate how Americans’ retirement savings have evolved over the decades, Guideline compiled a timeline on the evolution of the 401(k), drawing on research from the Employee Benefit Research Institute, the Investment Company Institute, and legislative records.

![]()

Debrocke/ClassicStock // Getty Images

Pre-1978: First, there were CODAs

Before the mighty 401(k) there were Cash or Deferred Arrangements, commonly known as CODAs.

These arrangements between companies and workers allowed employees to defer some of their income and the taxes they paid on it for a period of time. CODAs were a funding mechanism for stock bonus, pension, and profit-sharing plans.

In 1974, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) was enacted, creating a governmental body that oversaw and regulated company-sponsored retirement and health care plans for workers.

ERISA temporarily halted IRS plans to severely restrict retirement plans through regulation in the early 1970s, according to the EBRI. The act created a study of employee salary reduction plans as well, which the EBRI credits for influencing the creation of the 401(k) later on in the decade.

Harold M. Lambert // Getty Images

1978: The Revenue Act of 1978

The modern 401(k) originated in earnest in 1978 with a provision in The Revenue Act of 1978 which said that employees can choose to receive a portion of income as deferred compensation, and created tax structures around it.

Section 401 was originally intended by lawmakers to limit companies creating tax-advantaged profit-sharing plans that mostly benefited executives, according to the ICI. Thanks to the interpretation of the section by businessman Ted Benna, the language evolved into the basis of the modern 401(k), as it enabled profit-sharing plans to adopt CODAs.

The law was signed by President Jimmy Carter and became effective at the turn of the decade. Regulations were then created and issued by the end of 1981.

The Revenue Act of 1978 not only created the foundation for 401(k) savings plans but also flexible spending accounts for medical expenses and the independent contractor classification as it pertains to how a company pays employment taxes.

Nicholas Hunt // Getty Images

1980: “Father of the 401(k)” Ted Benna first implements the retirement plan

Ted Benna, pictured above, is popularly known as the “Father of the 401(k)” for his work advocating for companies to adopt plans in accordance with the IRS’ new Revenue Act of 1978.

His self-described “aggressive” interpretation of the eponymous 401(k) section within the Act led him to create the first-ever 401(k) savings plan in the U.S. for his consulting company.

Through business connections, Benna was introduced to Treasury officials and provided recommendations as to how 401(k) should be regulated. Ultimately, Benna was able to help steer the success and adoption of the nascent retirement tool.

Today, Benna advocates for laws that would require employers to auto-enroll their workers in 401(k) plans, meaning employers would automatically deduct payroll deferrals unless an employee elects not to participate. One of the biggest downsides to 401(k) plans is actually that more workers don’t utilize them sooner in their careers. The earlier a person starts contributing money to one of these retirement accounts, the better positioned they are to significantly grow funds by their target retirement age.

While 68% of private sector American workers had access to employee-sponsored retirement plans in 2021, only about half of all Americans took advantage of one.

Barbara Alper // Getty Images

1981: IRS clarification leads major companies to adopt 401(k) policies

In the late 1970s, pioneering aviation company Hughes Aircraft was well on its way to becoming the largest industrial employer in the state of California. The company’s outside legal consultant Ethan Lipsig was writing letters to Hughes Aircraft, encouraging the company to turn the savings plan it offered employees into a 401(k) plan.

But it wasn’t until the IRS issued regulations assuring employers that they could legally defer a portion of payroll compensation to a 401(k) savings account that companies like Hughes, J.C. Penney, Johnson & Johnson, and PepsiCo began offering the plans to workers.

Nearly half of all large employers in the U.S. were offering 401(k) plans to their workers by the end of 1982.

MPI // Getty Images

1984-1986: The Tax Reform Acts of 1984 and 1986

In 1984 and again in 1986 U.S. lawmakers, pictured above, made amendments to the country’s tax code sometimes referred to today as the “Reagan tax cuts.”

In 1984, laws were amended as part of the so-called Deficit Reduction Act to tighten the rules around deferred compensation, including 401(k) savings plans. The legislation ensured that less highly compensated employees could also benefit from plans—not just the highest paid workers. In a brief published in September 1985, the EBRI expressed concern that Reagan’s amendment could jeopardize the popularity of 401(k) savings plans.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 consolidated tax brackets, lowered federal income taxes, and placed an annual limit on deferred compensation, according to the EBRI. It had the added benefit of “endorsing” the 401(k) as a legitimate retirement vehicle because the Act implemented a 401(k)-type plan for federal employees.

David Hume Kennerly // Getty Images

1996: The Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996

The Small Business Job Protection Act came along in 1996 and simplified retirement programs—called SIMPLE plans—for small businesses. The act signed into law by President Bill Clinton was intended to help make America’s small businesses more competitive with large firms.

It specifically made the employer-matching contribution process easier through SIMPLE plans for businesses with fewer than 100 employees. The act also lowered taxes for small businesses, created safe-harbor formulas to eliminate the need for nondiscrimination testing, simplified pensions, and raised the minimum wage.

Mark Wilson // Getty Images

2001: The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act

The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act paved the way for many changes including allowing catch-up contributions for employees aged 50 and older, requiring faster vesting timeframes for matching contributions, and, perhaps most notably, introducing the Roth 401(k).

Officially launched to the public in 2006, a Roth 401(k) is employer-sponsored like a traditional 401(k). The account holder elects to contribute a portion of their income to the account, and the employer has the option to contribute matching funds.

The difference is that contributions are taxed before they go into the Roth account, which means that the owner doesn’t have to pay taxes again when they withdraw from the account after they are aged 59 and a half or older. At its core, the Roth 401(k) gives the owner the advantage of paying taxes now instead of being taxed on withdrawals later in life when the account is worth more monetarily—or when future tax rates may have increased.

Millennials are more likely to contribute to Roth 401(k)s than older generations, according to a 2019 report from the Transamerica Center for Retirement Studies.

Tom Williams // Getty Images

2022: The Securing a Strong Retirement Act is making its way through Congress

Flash forward to the current day and much has changed about planning for retirement. Pensions have all but disappeared and many Americans continue to redefine what retirement will look like for them — and how to plan ahead for it. In the U.S., people live on average 10 years longer today than they did when the 401(k) was created in 1978, and recent research suggests that generations younger than baby boomers may live longer than their retirement accounts will support them. So it’s more important than ever that people stay on top of changes in their retirement planning. As more tools, technology, and resources became available for learning and investing, legislation has also been introduced to help Americans navigate retirement decisions.

The Senate is currently debating a set of bills collectively referred to as “SECURE 2.0,” as they build on the SECURE Act passed in 2019. Among other changes, the 2019 legislation made it so part-time workers could participate in retirement plans and made offering plans more appealing for small businesses that may have been hesitant in the past.

SECURE 2.0 goes further to make employee enrollment in a retirement savings plan like a 401(k) mandatory. It would also alter rules around making late contributions to payments so that Americans older than 50 can contribute even more than previously to their accounts.

This story originally appeared on Guideline and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

You may like

Business

Cashiers vs. digital ordering: What do people want, and at what cost?

Published

5 days agoon

April 26, 2024

You walk into a fast-food restaurant on your lunch break. You don’t see a cashier but instead a self-service kiosk, a technology that is becoming the new norm in eateries across the country. The kiosks usually offer customers a menu to scroll through and pictures of meals and specials with prompts to select their food and submit their payment in one place.

Self-service kiosks are big business. In fact, the market for self-service products is expected to grow from a $40.3 billion market value in 2022 to $63 billion by 2027, according to a report from BCC Research. Consumers do have mixed opinions about the kiosks, but about 3 out of 5 surveyed consumers reported that they were likely to use self-service kiosks, according to the National Restaurant Association. The technology, while expensive, can boost businesses’ bottom lines in the long run.

Task Group summarized the rise in digital ordering over the past couple of years, its acceptance among customers, and a cost analysis of adopting the technology.

Self-service kiosks—digital machines or display booths—are generally placed in high-traffic areas. They can be used for different reasons, including navigating a store or promoting a product. Interactive self-service kiosks in particular are meant for consumers to place orders with little to no assistance from employees.

The idea of kiosks isn’t new. The concept of self-service was first introduced in the 1880s when the first types of kiosks appeared as vending machines selling items like gum and postcards. In the present age of technology, the trend of self-service has only grown. Restaurants such as McDonald’s and Starbucks have already tried out cashierless technology.

From a business perspective, the kiosks offer a huge upside. While many employers are looking for workers, they’re having a hard time finding staff. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, employers struggled with a severe employee shortage. Since then, the problem has continued. In 2022, the National Restaurant Association reported that 65% of restaurant operators didn’t have enough workers on staff to meet consumer demand. With labor shortages running rampant, cashierless technology could help restaurants fill in for the lack of human employees.

The initial investment for the kiosks can be high. The general cost per kiosk is difficult to quantify, with one manufacturer estimating a range of $1,500 to $20,000 per station. However, with the use of kiosks, restaurants may not need as many cashiers or front-end employees, instead reallocating workers’ time to other tasks.

In May 2022, the hourly mean wage for cashiers who worked in restaurants and other eating establishments was $12.99, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Kiosks could cost less money than a cashier in the long run.

But how do the customers themselves feel about the growing trend? According to a Deloitte survey, 62% of respondents report that they were “somewhat likely” to order from a cashierless restaurant if given the chance to do so. The same survey reported that only 19% of respondents had experience with a cashierless restaurant.

What would it mean for society if restaurants did decide to go completely cashierless? Well, millions of positions would likely no longer be necessary. One report suggests 82% of restaurant positions could be replaced by robots, a prospect making automation appealing to owners who can’t find staff to hire.

Due to the ongoing labor shortage, employers have tried raising employee wages. Papa John’s, Texas Roadhouse, and Chipotle were among the restaurant companies that increased employee pay or offered bonuses in an attempt to hire and retain more workers. Meanwhile, some companies have decided to use technology to perform those jobs instead, so that they wouldn’t have to put effort into hiring or focus their existing staff on other roles.

Story editing by Ashleigh Graf and Jeff Inglis. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.

![]()

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

It’s well-documented that the surest, and often best, return on investments comes from playing the long game. But between stocks and real estate, which is the stronger bet?

To find out, financial planning firm Wealth Enhancement Group analyzed data from academic research, Standard and Poor’s, and Nareit to see how real estate compares to stocks as an investment.

Data going back to 1870 shows the well-established power of real estate as a powerful “long-run investment.” From 1870-2015, and after adjusting for inflation, real estate produced an average annual return of 7.05%, compared to 6.89% for equities. These findings, published in the 2019 issue of The Quarterly Journal of Economics, illustrate that stocks can deviate as much as 22% from their average, while housing only spreads out 10%. That’s because despite having comparable returns, stocks are inherently more volatile due to following the whims of the business cycle.

Real estate has inherent benefits, from unlocking cash flow and offering tax breaks to building equity and protecting investors from inflation. Investments here also help to diversify a portfolio, whether via physical properties or a real estate investment trust. Investors can track markets with standard resources that include the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Home Price Indices, which tracks residential real estate prices; the Nareit U.S. Real Estate Index, which gathers data on the real estate investment trust, or REIT, industry; and the S&P 500, which tracks the stocks of 500 of the largest companies in the U.S.

High interest rates and a competitive market dampened the flurry of real-estate investments made in the last four years. The rise in interest rates equates to a bigger borrowing cost for investors, which can spell big reductions in profit margins. That, combined with the risk of high vacancies, difficult tenants, or hidden structural problems, can make real estate investing a less attractive option—especially for first-time investors.

Keep reading to learn more about whether real estate is a good investment today and how it stacks up against the stock market.

![]()

Wealth Enhancement Group

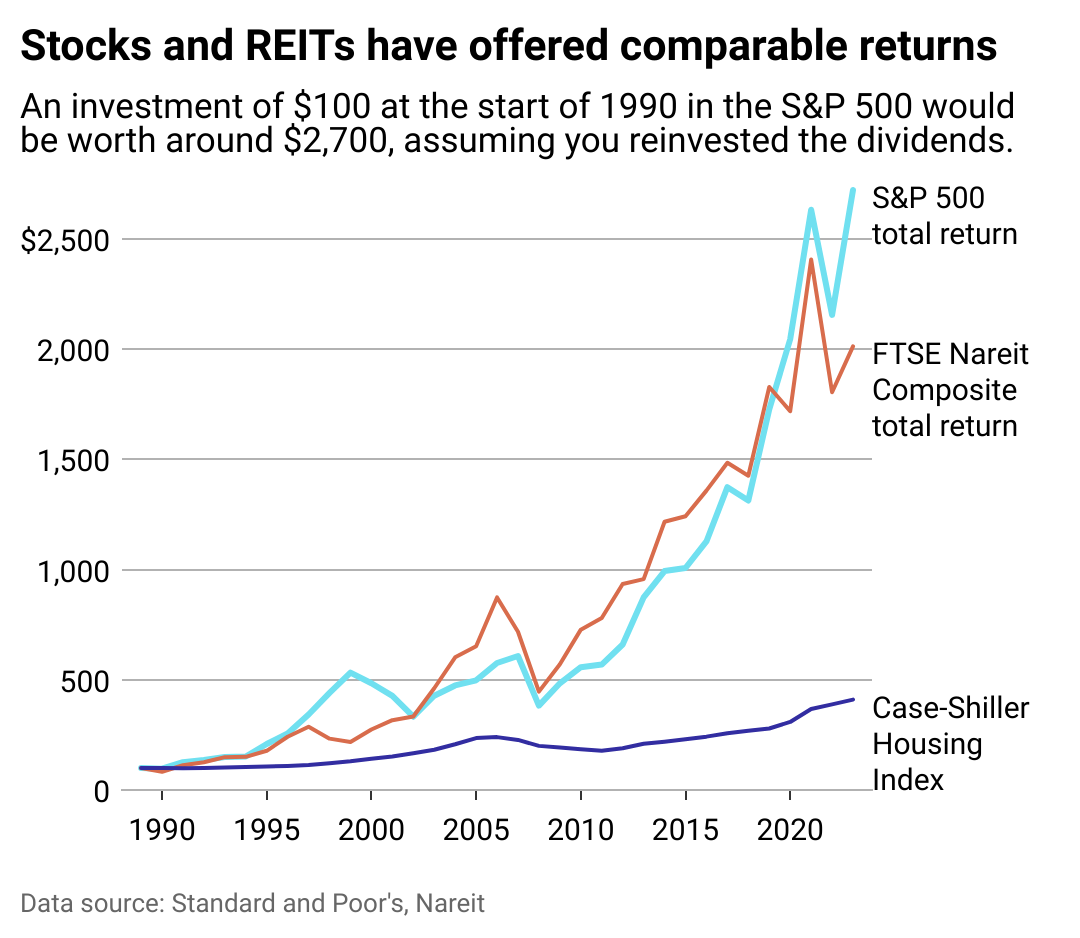

Stocks and housing have both done well

REITs can offer investors the stability of real estate returns without bidding wars or hefty down payments. A hybrid model of stocks and real estate, REITs allow the average person to invest in businesses that finance or own income-generating properties.

REITs delivered slightly better returns than the S&P 500 over the past 20-, 25-, and 50-year blocks. However, in the short term—the last 10 years, for instance—stocks outperformed REITs with a 12% return versus 9.5%, according to data compiled by The Motley Fool investor publication.

Whether a new normal is emerging that stocks will continue to offer higher REITs remains to be seen.

This year, the S&P 500 reached an all-time high, courtesy of investor enthusiasm in speculative tech such as artificial intelligence. However, just seven tech companies, dubbed “The Magnificent 7,” are responsible for an outsized amount of the S&P’s returns last year, creating worry that there may be a tech bubble.

While indexes keep a pulse on investment performance, they don’t always tell the whole story. The Case-Shiller Index only measures housing prices, for example, which leaves out rental income (profit) or maintenance costs (loss) when calculating the return on residential real estate investment.

Wealth Enhancement Group

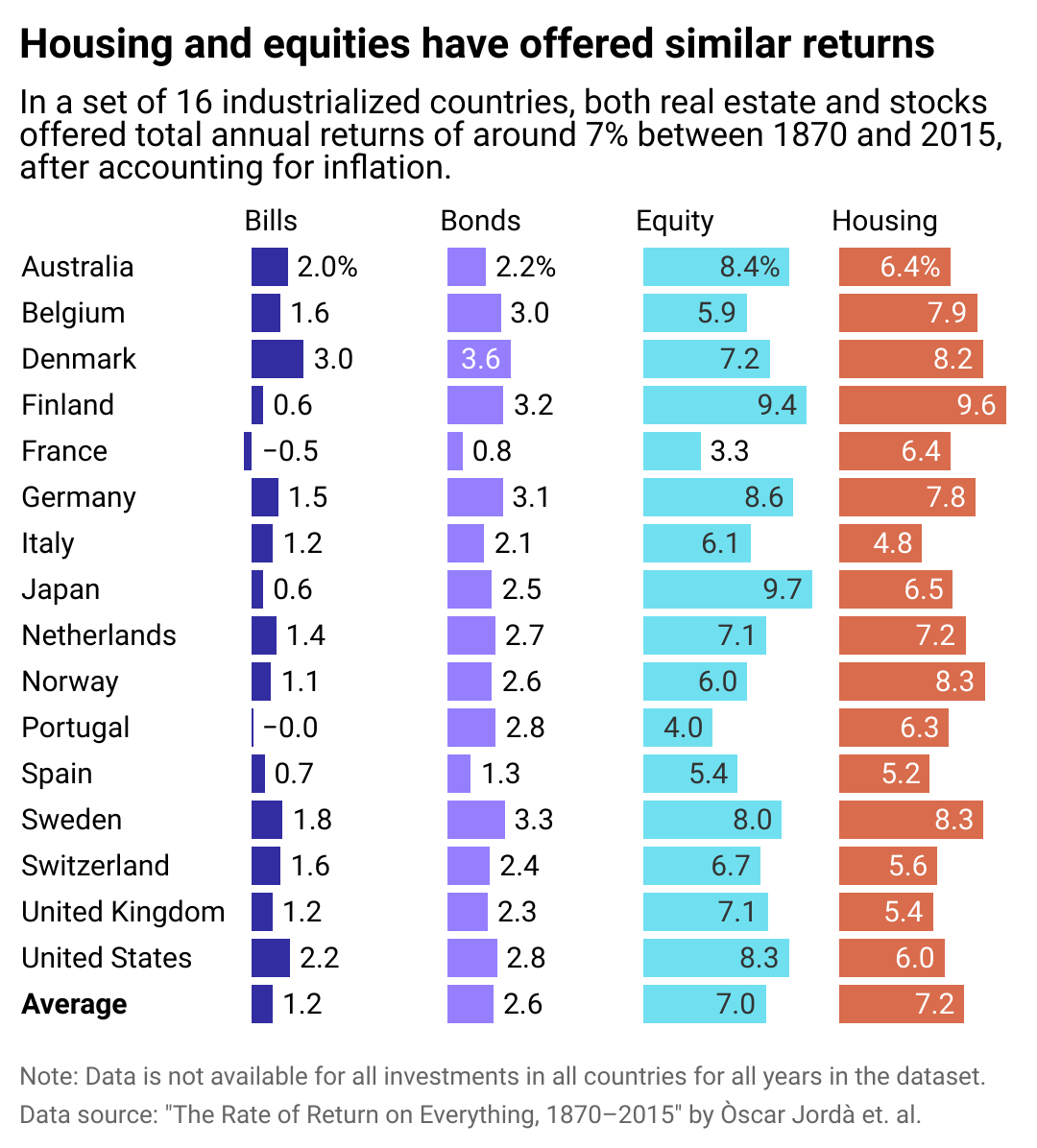

Housing returns have been strong globally too

Like its American peers, the global real estate market in industrialized nations offers comparable returns to the international stock market.

Over the long term, returns on stocks in industrialized nations is 7%, including dividends, and 7.2% in global real estate, including rental income some investors receive from properties. Investing internationally may have more risk for American buyers, who are less likely to know local rules and regulations in foreign countries; however, global markets may offer opportunities for a higher return. For instance, Portugal’s real estate market is booming due to international visitors deciding to move there for a better quality of life. Portugal’s housing offers a 6.3% return in the long term, versus only 4.3% for its stock market.

For those with deep enough pockets to stay in, investing in housing will almost always bear out as long as the buyer has enough equity to manage unforeseen expenses and wait out vacancies or slumps in the market. Real estate promises to appreciate over the long term, offers an opportunity to collect rent for income, and allows investors to leverage borrowed capital to increase additional returns on investment.

Above all, though, the diversification of assets is the surest way to guarantee a strong return on investments. Spreading investments across different assets increases potential returns and mitigates risk.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Wealth Enhancement Group and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Business

5 tech advancements sports venues have added since your last event

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 19, 2024

In today’s digital climate, consuming sports has never been easier. Thanks to a plethora of streaming sites, alternative broadcasts, and advancements to home entertainment systems, the average fan has myriad options to watch and learn about their favorite teams at the touch of a button—all without ever having to leave the couch.

As a result, more and more sports venues have committed to improving and modernizing their facilities and fan experiences to compete with at-home audiences. Consider using mobile ticketing and parking passes, self-service kiosks for entry and ordering food, enhanced video boards, and jumbotrons that supply data analytics and high-definition replays. These innovations and upgrades are meant to draw more revenue and attract various sponsored partners. They also deliver unique and convenient in-person experiences that rival and outmatch traditional ways of enjoying games.

In Los Angeles, the Rams and Chargers’ SoFi Stadium has become the gold standard for football venues. It’s an architectural wonder with closer views, enhanced hospitality, and a translucent roof that cools the stadium’s internal temperature.

The Texas Rangers’ ballpark, Globe Life Field, added field-level suites and lounges that resemble the look and feel of a sports bar. Meanwhile, the Los Angeles Clippers are building a new arena (in addition to retail space, team offices, and an outdoor public plaza) that will seat 18,000 people and feature a fan section called The Wall, which will regulate attire and rooting interest.

It’s no longer acceptable to operate with old-school facilities and technology. Just look at Commanders Field (formerly FedExField), home of the Washington Commanders, which has faced criticism for its faulty barriers, leaking ceilings, poor food options, and long lines. Understandably, the team has been attempting to find a new location to build a state-of-the-art stadium and keep up with the demand for high-end amenities.

As more organizations audit their stadiums and arenas and keep up with technological innovations, Uniqode compiled a list of the latest tech advancements to coax—and keep—fans inside venues.

![]()

Jeff Gritchen/MediaNews Group/Orange County Register // Getty Images

Just Walk Out technology

After successfully installing its first cashierless grocery store in 2020, Amazon has continued to put its tracking technology into practice.

In 2023, the Seahawks incorporated Just Walk Out technology at various merchandise stores throughout Lumen Field, allowing fans to purchase items with a swipe and scan of their palms.

The radio-frequency identification system, which involves overhead cameras and computer vision, is a substitute for cashiers and eliminates long lines.

RFID is now found in a handful of stadiums and arenas nationwide. These stores have already curbed checkout wait times, eliminated theft, and freed up workers to assist shoppers, according to Jon Jenkins, vice president of Just Walk Out tech.

Billie Weiss/Boston Red Sox // Getty Images

Self-serve kiosks

In the same vein as Amazon’s self-scanning technology, self-serve kiosks have become a more integrated part of professional stadiums and arenas over the last few years. Some of these function as top-tier vending machines with canned beers and nonalcoholic drinks, shuffling lines quicker with virtual bartenders capable of spinning cocktails and mixed drinks.

The kiosks extend past beverages, as many college and professional venues have started using them to scan printed and digital tickets for more efficient entrance. It’s an effort to cut down lines and limit the more tedious aspects of in-person attendance, and it’s led various competing kiosk brands to provide their specific conveniences.

Kyle Rivas // Getty Images

Mobile ordering

Is there anything worse than navigating the concourse for food and alcohol and subsequently missing a go-ahead home run, clutch double play, or diving catch?

Within the last few years, more stadiums have eliminated those worries thanks to contactless mobile ordering. Fans can select food and drink items online on their phones to be delivered right to their seats. Nearly half of consumers said mobile app ordering would influence them to make more restaurant purchases, according to a 2020 study at PYMNTS. Another study showed a 22% increase in order size.

Many venues, including Yankee Stadium, have taken notice and now offer personalized deliveries in certain sections and established mobile order pick-up zones throughout the ballpark.

Darrian Traynor // Getty Images

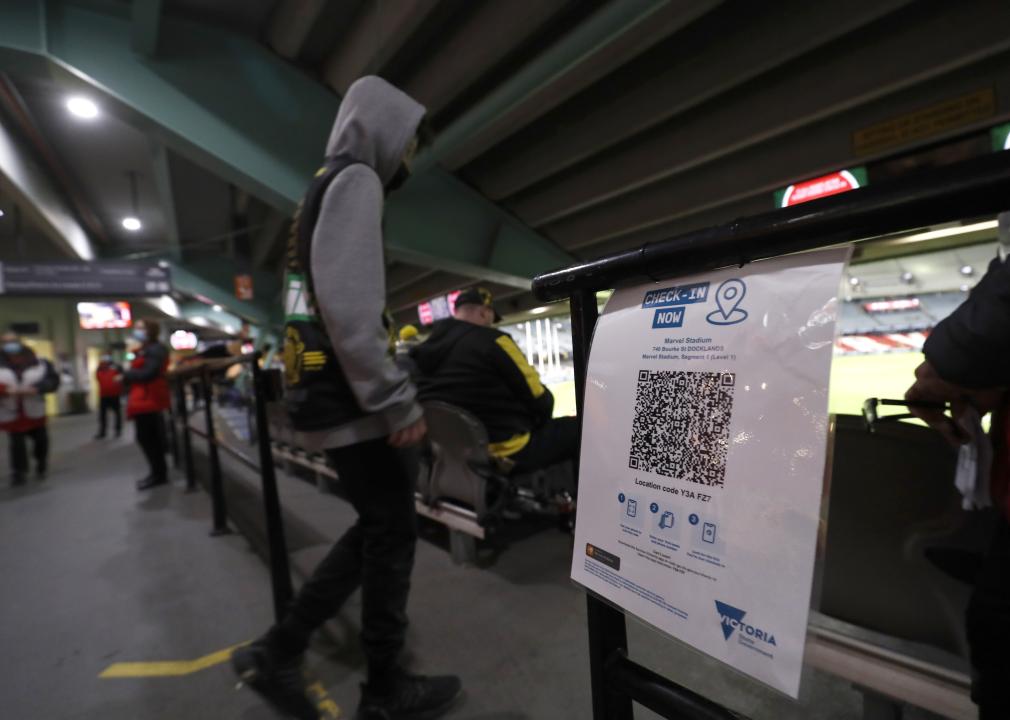

QR codes at seats

Need to remember a player’s name? Want to look up an opponent’s statistics at halftime? The team at Digital Seat Media has you covered.

Thus far, the company has added seat tags to more than 50 venues—including two NFL stadiums—with QR codes to promote more engagement with the product on the field. After scanning the code, fans can access augmented reality features, look up rosters and scores, participate in sponsorship integrations, and answer fan polls on the mobile platform.

Boris Streubel/Getty Images for DFL // Getty Images

Real-time data analytics and generative AI

As more venues look to reinvigorate the in-stadium experience, some have started using generative artificial intelligence and real-time data analytics. Though not used widely yet, generative AI tools can create new content—text, imagery, or music—in conjunction with the game, providing updates, instant replays, and location-based dining suggestions

Last year, the Masters golf tournament even began including AI score projections in its mobile app. Real-time data is streamlining various stadium pitfalls, allowing operation managers to monitor staffing issues at busy food spots, adjust parking flows, and alert custodians to dirty or damaged bathrooms. The data also helps with security measures. Open up an app at a venue like the Honda Center in Anaheim, California, and report safety issues or belligerent fans to help better target disruptions and preserve an enjoyable experience.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Paris Close. Photo selection by Lacy Kerrick.

This story originally appeared on Uniqode and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Founded in 2017, Stacker combines data analysis with rich editorial context, drawing on authoritative sources and subject matter experts to drive storytelling.

Featured

-

Business4 months ago

Business4 months agoSkill-based hiring is the answer to labour shortages, BCG report finds

-

Business5 months ago

Business5 months agomesh conference goes deep on AI, with experts focusing in on training, ethics, and risk

-

Events4 months ago

Events4 months agoThe Northern Lights Technology & Innovation Forum comes to Calgary next month

-

People4 months ago

People4 months agoHow connected technologies trim rework and boost worker safety in hands-on industries

-

Events5 months ago

Events5 months agoNavigating innovation, privacy policies, and diversity in a tech-driven world